5 November 2017

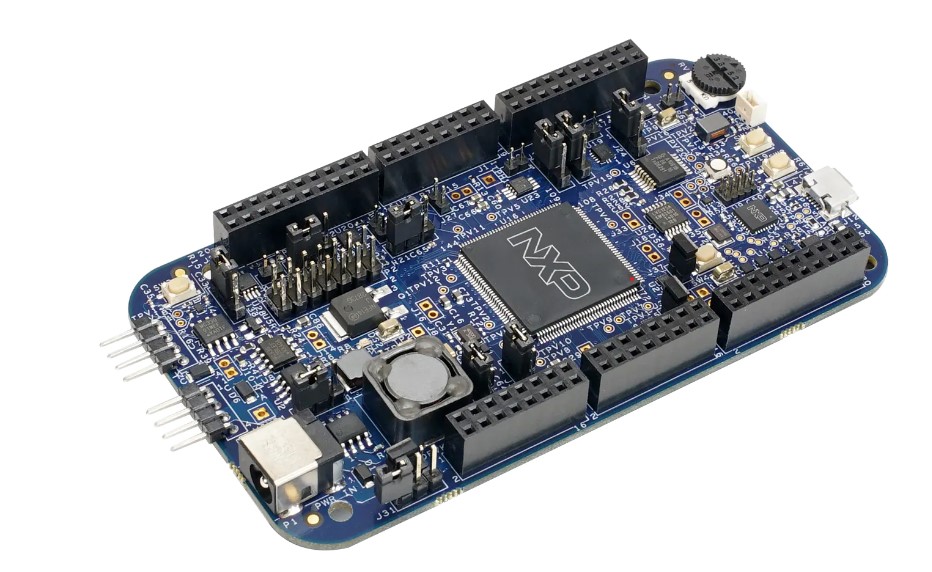

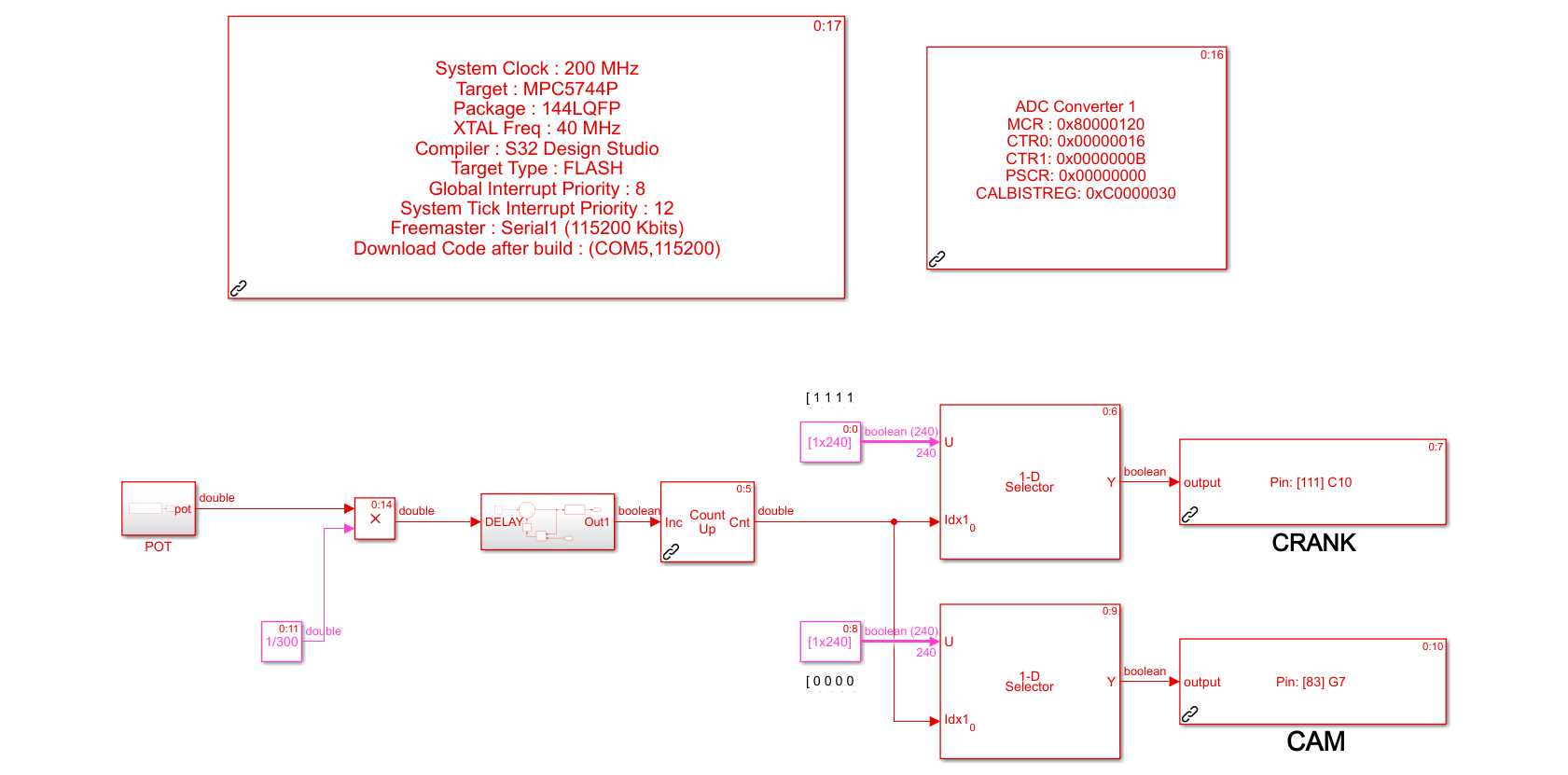

In my internship at BMC Power, my main project was to generate CAM/CRANK signals to emulate a running engine, using the NXP DEVKIT-MPC5744 and Simulink Embedded Coder. DEVKIT-MPC5744 is a development board for the MPC5744 chip, which is used in automotive and industrial functional safety and motor control applications. To achieve this, I used the NXP Model-Based Design Toolbox (MBDT).

My supervisor explained that my main project was to generate cam/crank signals to feed them to the ECU. When a motor is running, the cam and crank shafts rotate in a relationship. There are sensors attached to the ends of these shafts to measure their rotation speed and angle. These sensors usually work with induction, when a gear tooth passes by the sensor in high speeds, it generates a readable voltage. This results in a periodic waveform with peaks corresponding to every tooth head. The ECU can then calculate the rotation frequency and angle of cam/crank shafts; allowing it to know the exact instantaneous position of the gears. The ECU ultimately uses this data to determine and synchronize cylinder injections, spark timing and fuel delivery amounts; which are crucially time-sensitive to ensure maximum motor efficiency. After getting familiar with the board enough to generate these waveforms, they are then to be fed into a test ECU; tricking it to believe that these waveforms are actually coming from real sensors situated on a working engine.

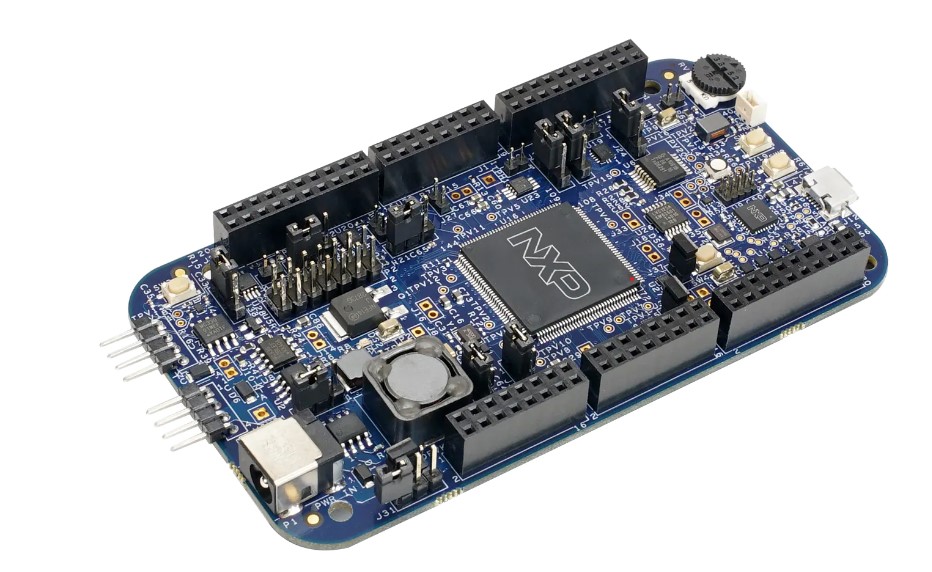

To begin, I coded a “Hello World!” equivalent in a development board in C. Here is my first code of a blinking blue LED. It is downloaded to the board via NXP’s own IDE, S32 Design Studio. Figure 6 shows the ON and OFF states of the LED. Here is the C code for reference:

#include "derivative.h"

#define MAXCNT 424242 // count limit.

extern void xcptn_xmpl(void);

int main(void)

{

volatile int counter = 0; // initialize counter.

xcptn_xmpl ();

SIUL2.MSCR[45].B.OBE = 1; // init LED.

for(;;) {

counter++;

if(counter == MAXCNT){

SIUL2.GPDO[45].R ^= 1; // if counter reaches limit, switch LED and reset counter.

counter = 0;

}

}

}

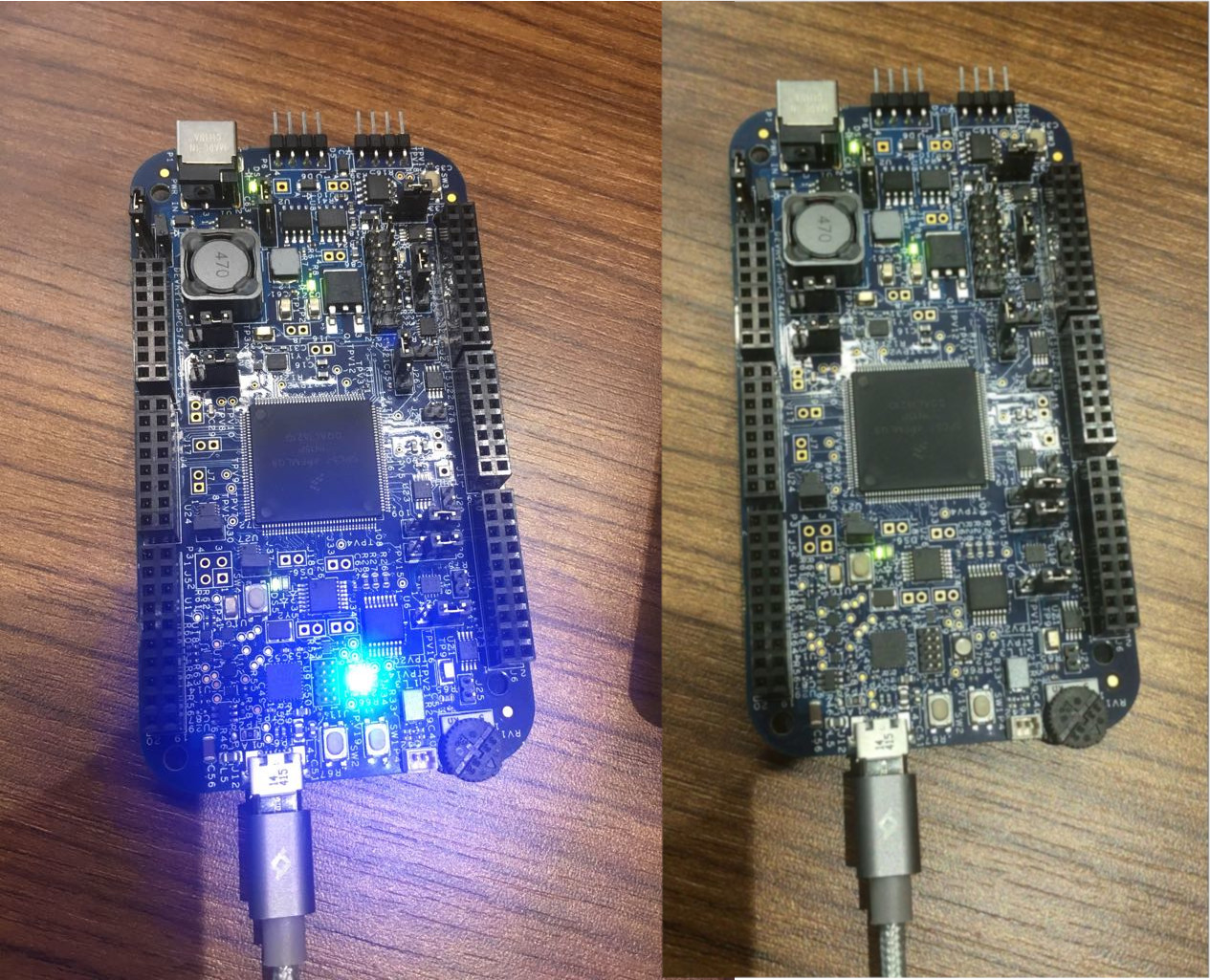

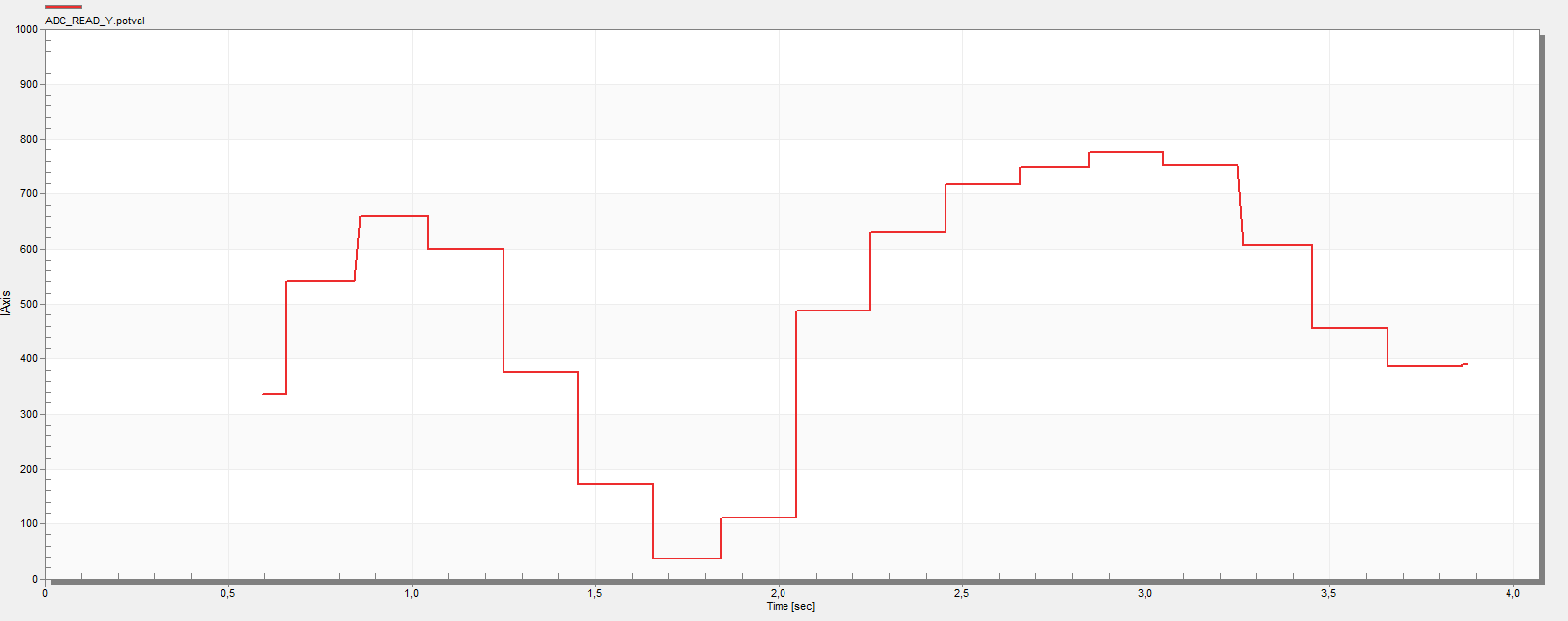

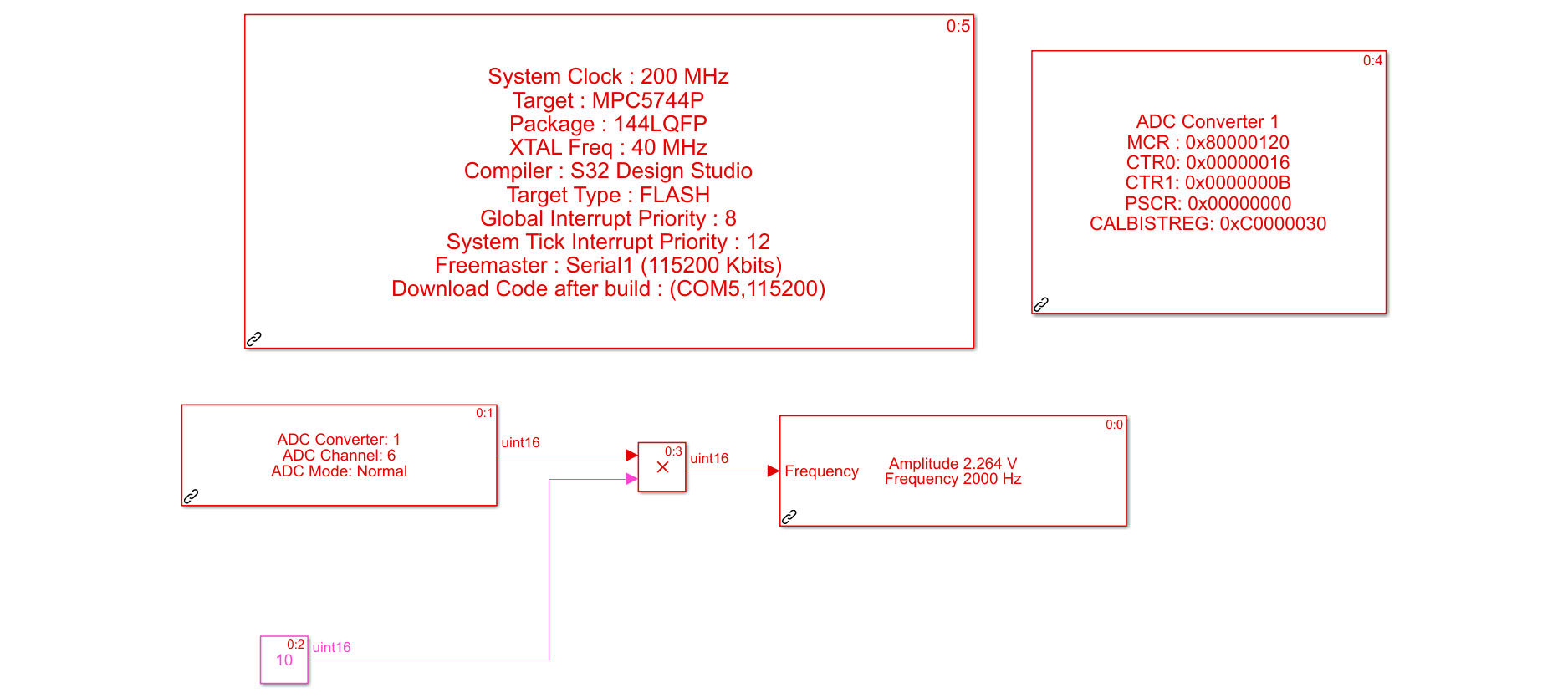

After doing a sanity-check on the board, my first project on SIMULINK was to make a program which takes the built-in pot as an analog input, converts it to digital, and shows the digital output value via a debugger tool called FreeMASTER. The built-in pot is connected to the pin PE12. By routing this as the input of the 12-bit ADC, I am able to read the pot’s value as an unsigned integer between 0 and 4096. I then observe and record this value using FreeMASTER. Figure 7 shows the model, and Figure 8 shows the value observed in FreeMASTER, changing while turning the pot. In my internship, I have heavily used the software FreeMASTER, so it is best to explain it in detail. While generating C-code from the SIMULINK blocks, you can configure the coder to also enable the FreeMASTER debug option, so the board outputs the real-time values of the signals out the serial ports. Normally you would connect these serial ports to your computer via a serial-USB converter (like CP2102), but since this is a development kit; I can get these signals directly from the USB interface. In FreeMASTER, I can choose which signals to “watch”, can display them using a scope, etc… So in case when one wants to monitor internal signal values in real time; this is really handy.

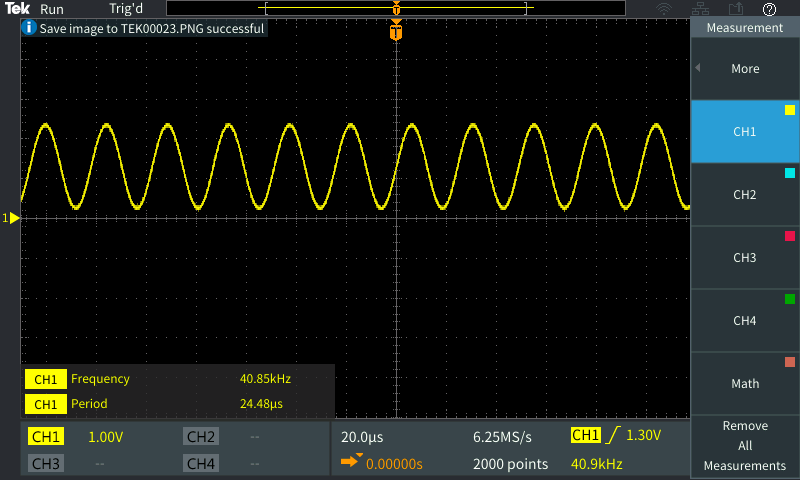

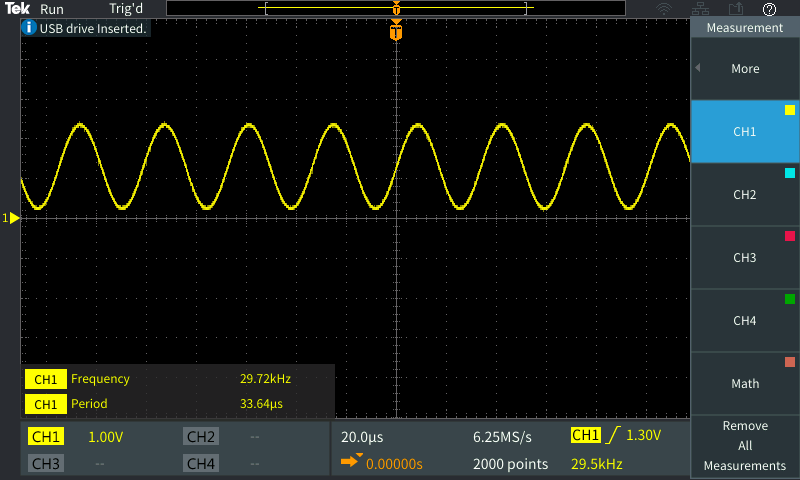

My next project was, using the uint16 (16-bit unsigned integer) value out of the pot, to output a sine signal with varying frequency depending on the pot value. After looking into the documentation, I added the sine wave generator in the MBDToolbox and connected the output of the pot (multiplied by 10) into the frequency input of this sine wave generator block. I probed output sine signal using the oscilloscope.

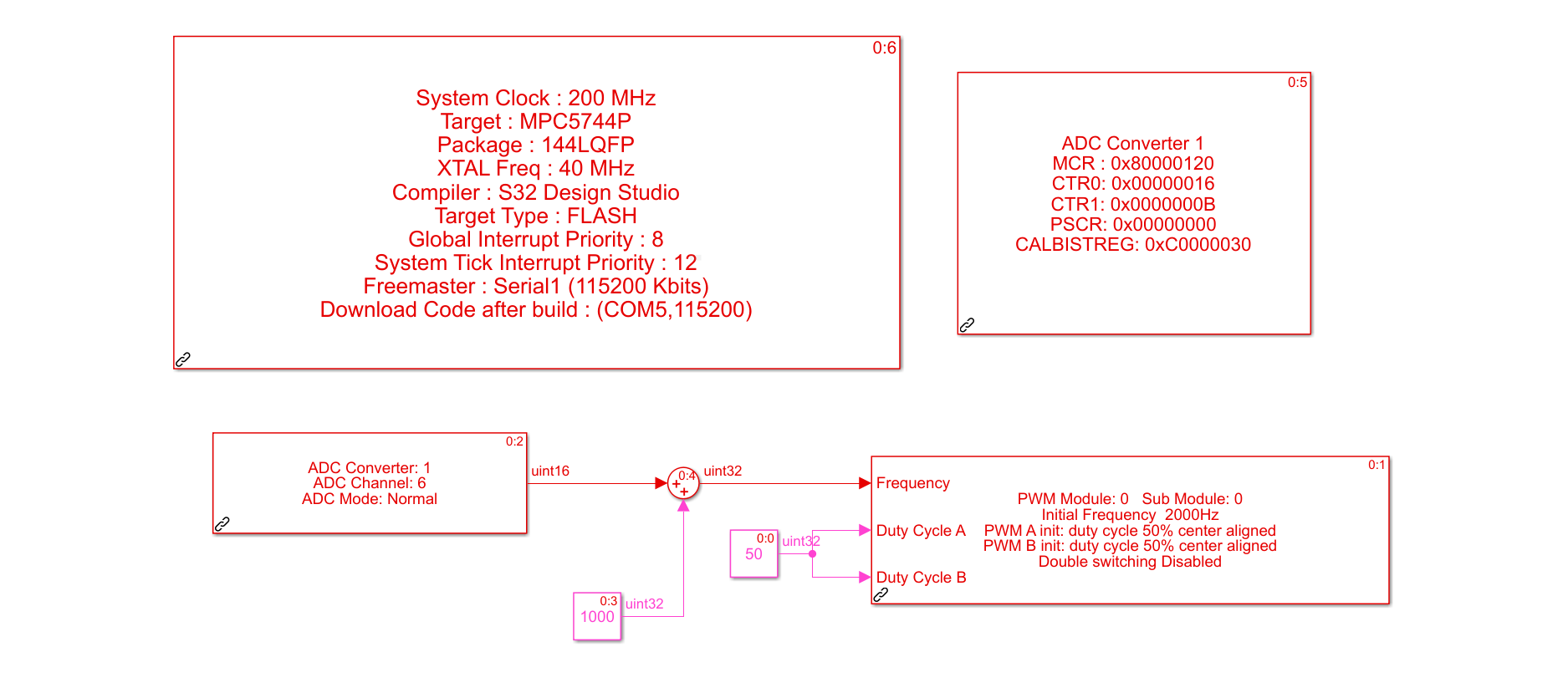

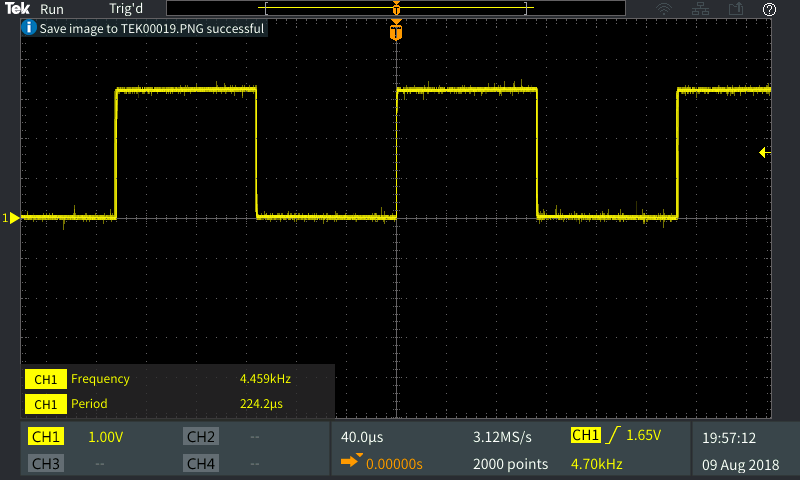

My next project was to generate a square wave output with varying frequency depending on the pot value. For this, I used the built-in PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) module, which allowed me to specify duty cycle and frequency as input ports. Connecting the output of pot to the frequency value similarly resulted in the correct waveform.

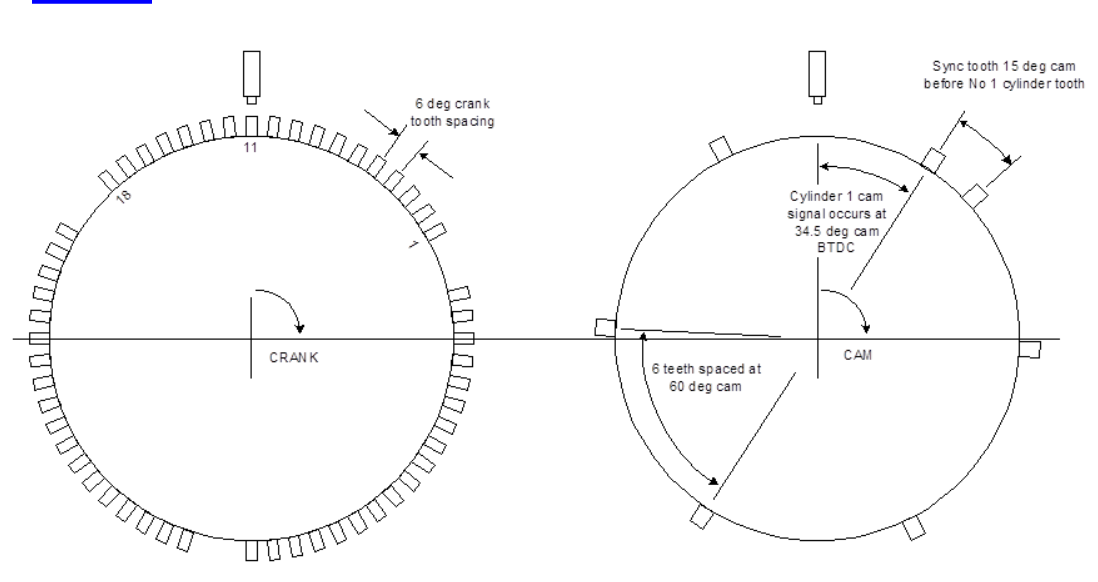

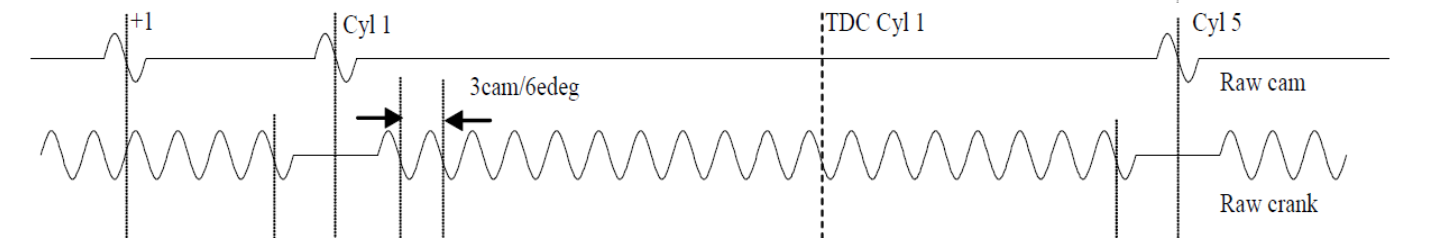

My next project was to design a square waveform with two “missing” peaks at the end of each period. This is required because the crankshaft sensor detects the teeth of the gear passing in front of it, and the gear has two consecutive teeth missing. This allows the ECU to know the exact position of the gear, and therefore the position of the crank mill - since the RPM is known. The last 2 missing teeth act as a marker. By examining the documentation from DELPHI corporation, which is the designer of the ECU we are going to test; I observed that the exact correlation between the crank/cam signals is as follows: as can be seen in Figure 15, the crankshaft gear has 60 teeth in total. But at the end of each 18 teeth, there are two teeth missing. So the signal is in the form of 18 peaks followed by two missing peaks. The camshaft signal is a little bit different. It has 7 peaks in 3 revolutions (720 degrees) of the crankshaft signal. The first 6 teeth are evenly spaced in the missing teeth of the crankshaft, the 7th, however, is 15 degrees before the first tooth. This results in an interesting waveform.

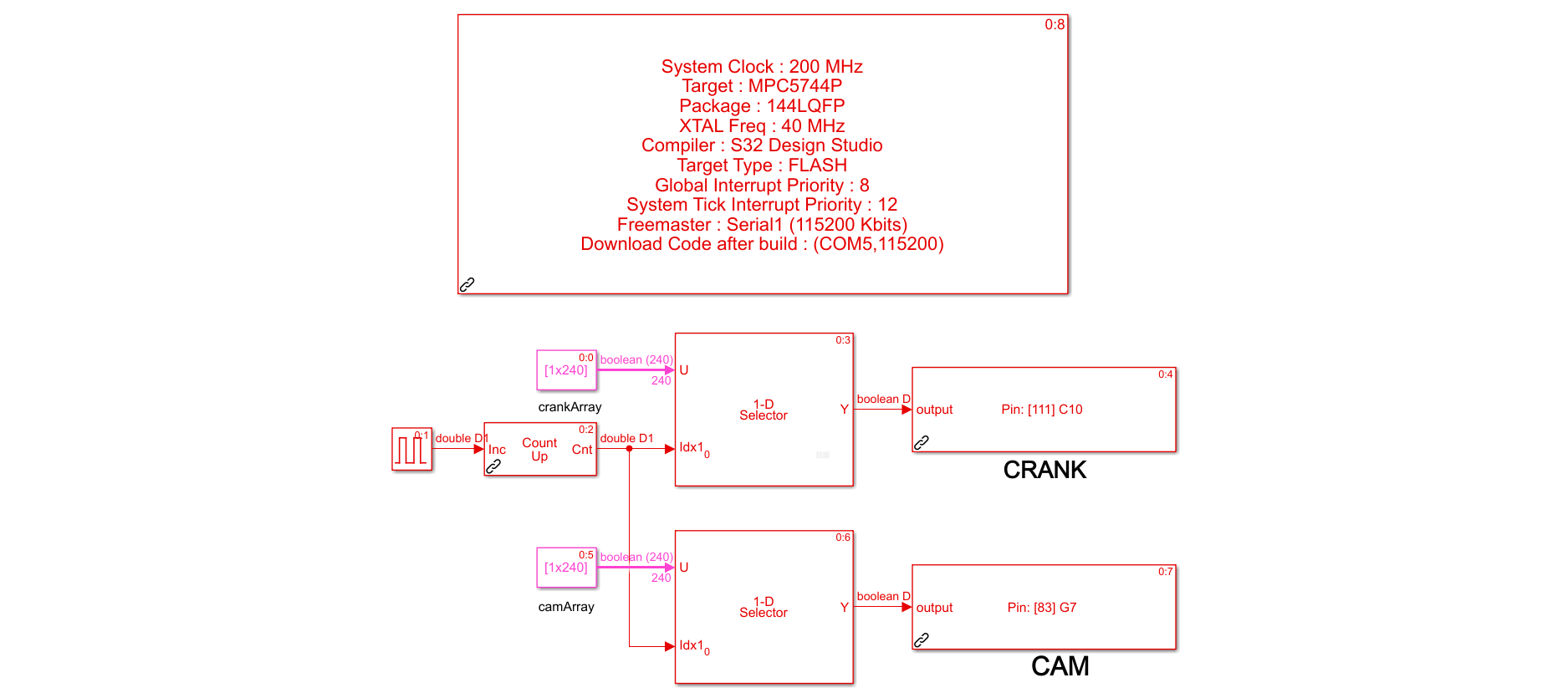

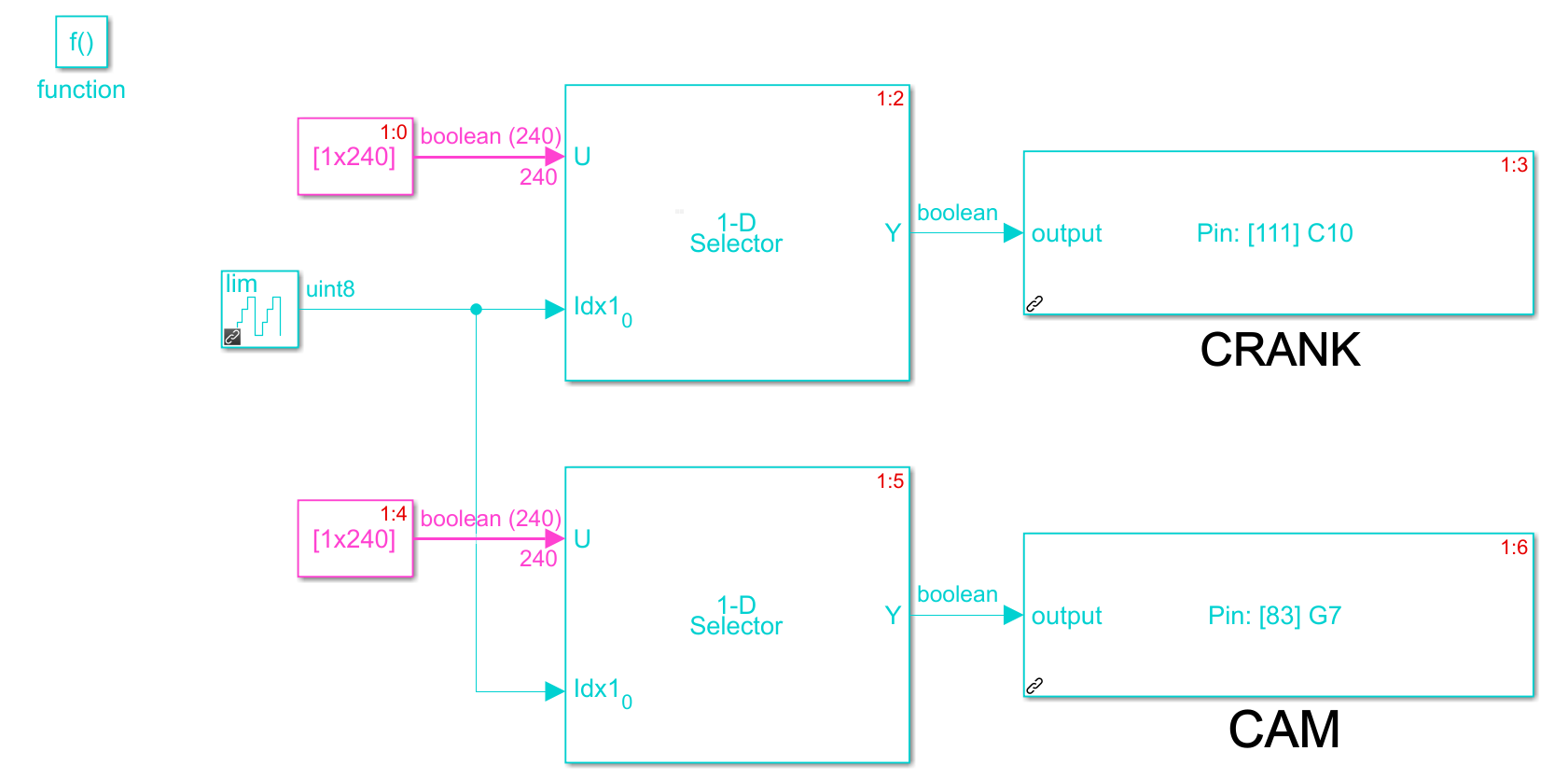

The PWM module in the toolbox does not have output ports so that I can modify the signal; it directly outputs the PWM signal out the board ports. So I had to come up with a way to generate the square signal from scratch so that it lacks the two wave peaks. As can be seen in Figure 17, I achieved this by creating an array consisting of 1’s and 0’s where the 1’s correspond to signals peaks and 0’s to zeroes. Then I used a selector to select the elements from this array consecutively. The selector block has an “index” input which dictates which index the selector should pick out of the array. I drove this index input with a counter block, which counts from 0 to the last index of the array, so that the selector block selects each element of the array in order, one by one. This counter has an input port called “increment”; which I set to be triggered at every rising edge. This way I can control the exact frequency of the counter; thus the waveform. This increment port is then finally driven by a pulse generator; acting as the clock.

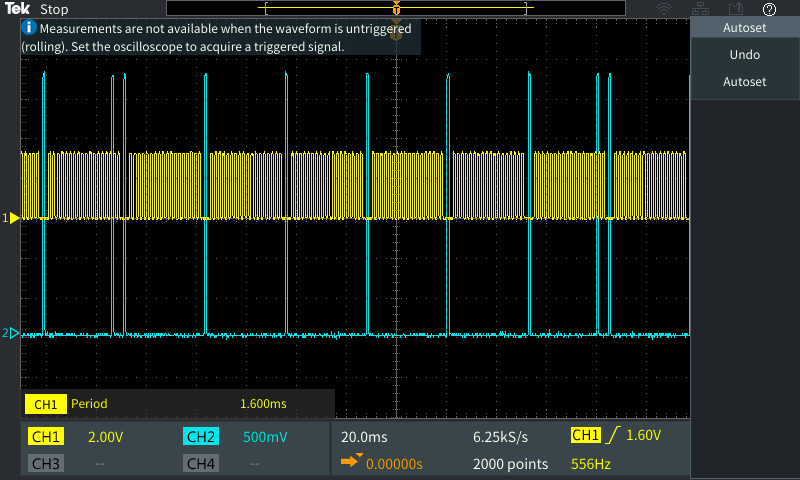

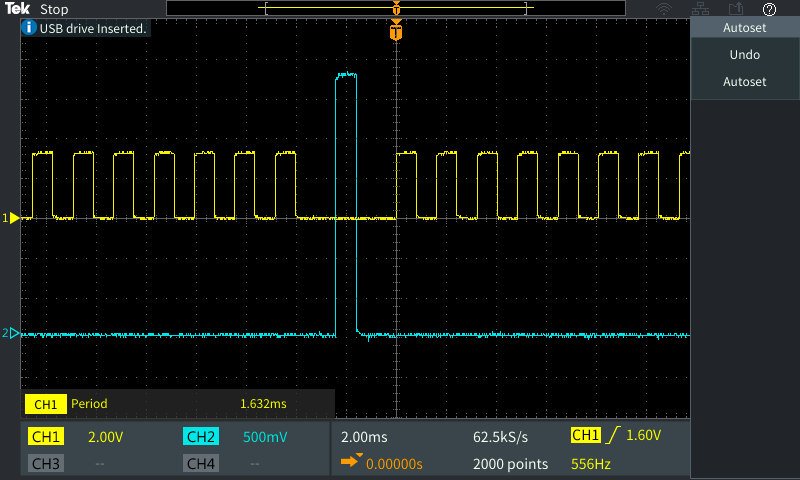

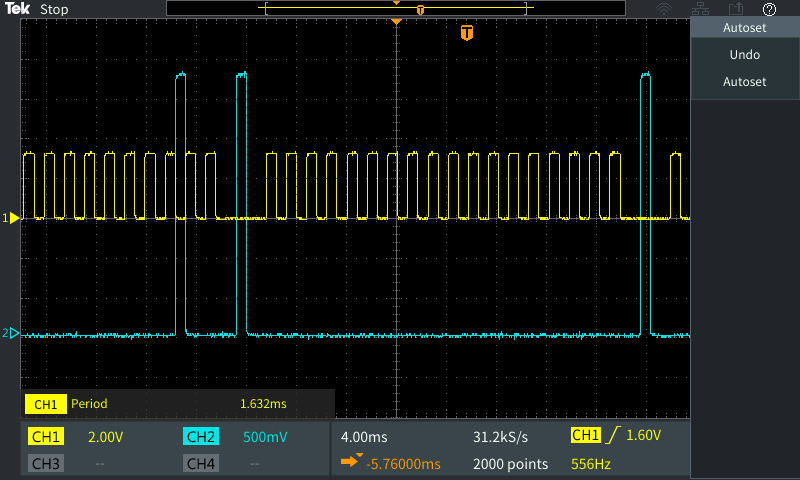

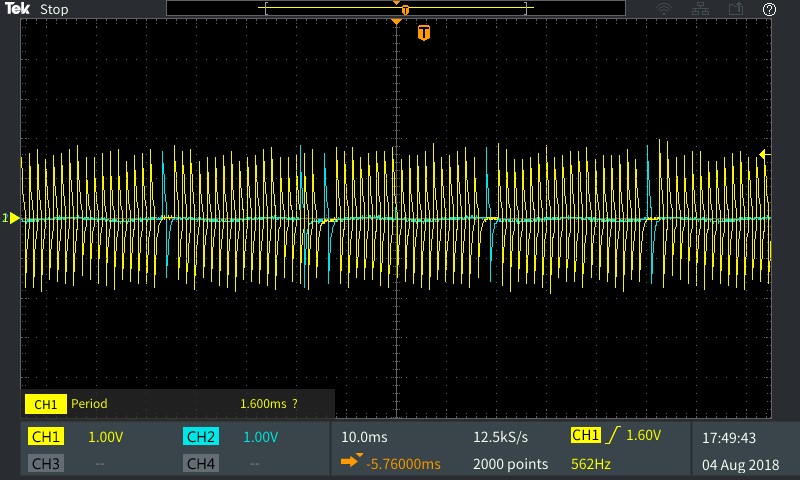

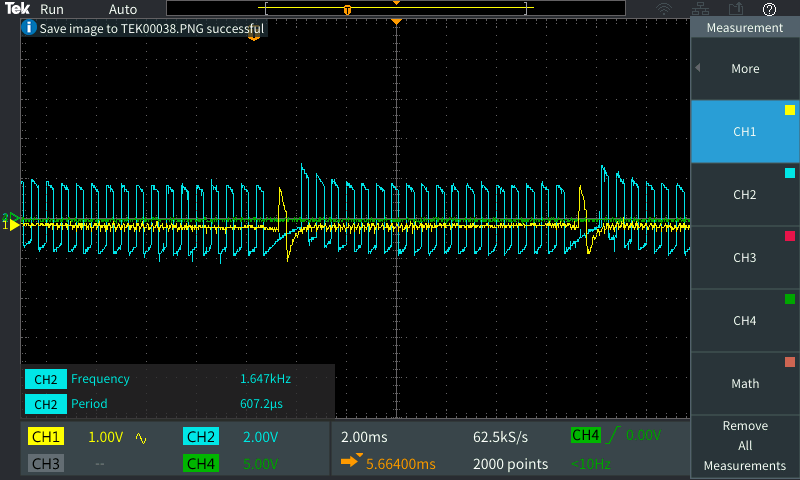

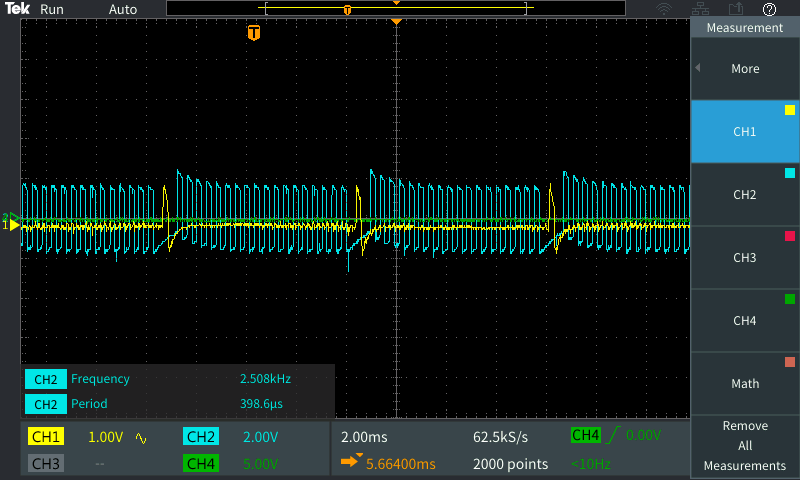

Figure 18 shows the observed waveforms of CAM (cyan) and CRANK (yellow) signals. As can be seen, the signals are in accordance with the configuration specified in the documents, where at each crank signal missing tooth period there is a cam signal peak, and there is also one extra peak 15 degrees before the last. The period of the crank signal is 1.6 ms, because the pulse generator clock is set to 0.8ms (since the selector block selects peaks and zeros, the period is doubled.). Figure 19 shows the CAM signal peak lining with the missing teeth. Figure 20 shows the 6th tooth just before the last.

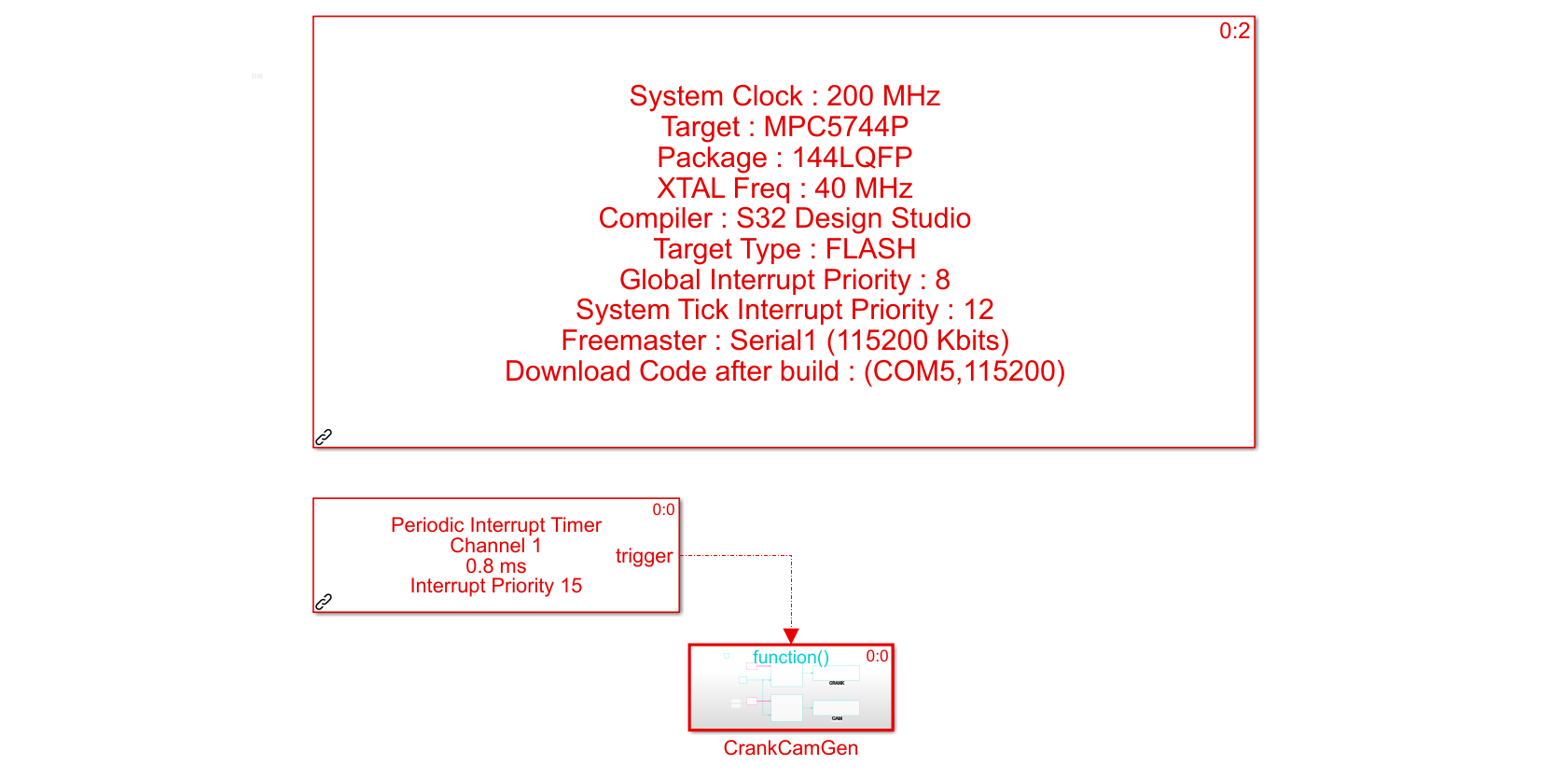

As another approach, I decided to use a PIT (Periodic-Interrupt-Timer) block to achieve more sensitive timings. A PIT block generates a “function-call” trigger event precisely at an interval of the provided time period. Using this “function-call” signal you can trigger a block or subsystem. I had to remove the pulse generator, replace the counter with a “trigger-less” version, and put the whole system in a “triggered subsystem” to be operated by the output of the PIT block. Setting the PIT interval to 0.8ms gave me a 1.6ms cam/crank waveform at the output (again, since the selector block selects peaks and zeros). The waveforms are the same, of course; it is, however, a better approach to use the built-in hardware timers for time-sensitive operations.

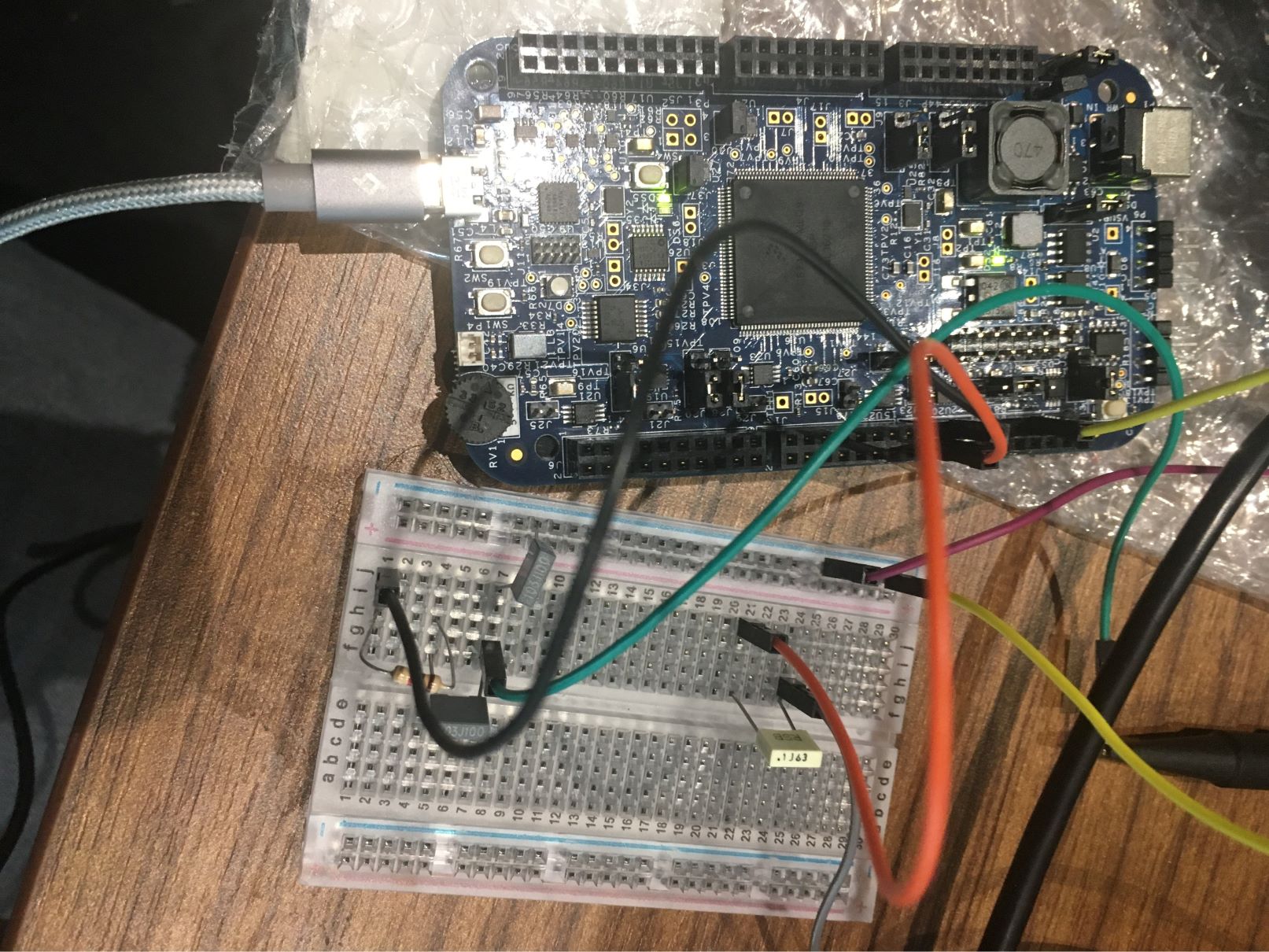

After generating the required waveforms, there was another problem. The output of the real engine sensors was with zero-crossings, and the ECU operated on these zero-crossings, not edge detection. However, our board has only digital output pins; this means a voltage value of either 0 or 3.3V; and so the waves did not cross zero. I had to pull the waveform down by -1.5V, or in other words, I had to eliminate a 1.5V DC offset. I achieved this via an HPF (High Pass Filter). If one imagines the DC offset as an infinitely low-frequency AC component, then it follows that an HPF would eliminate most of this component. Of course, the simplest HPF design is a capacitor in series with a resistor. Figure 23 shows the circuit on the breadboard. Using low valued capacitors, (22uF), I have managed to achieve correct and sharp zero-crossings; also the signal looked much more like real-world data than clean square waves due to the charge/discharge cycle introduced by the capacitors. Figures 24 and 25 show the modified CRANK CAM signals. Being convinced that these waveforms were acceptable; we moved on to test them on the ECU.

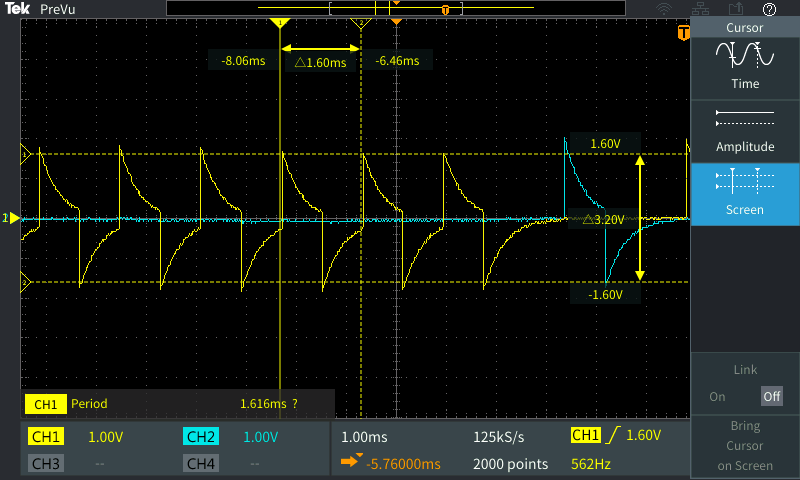

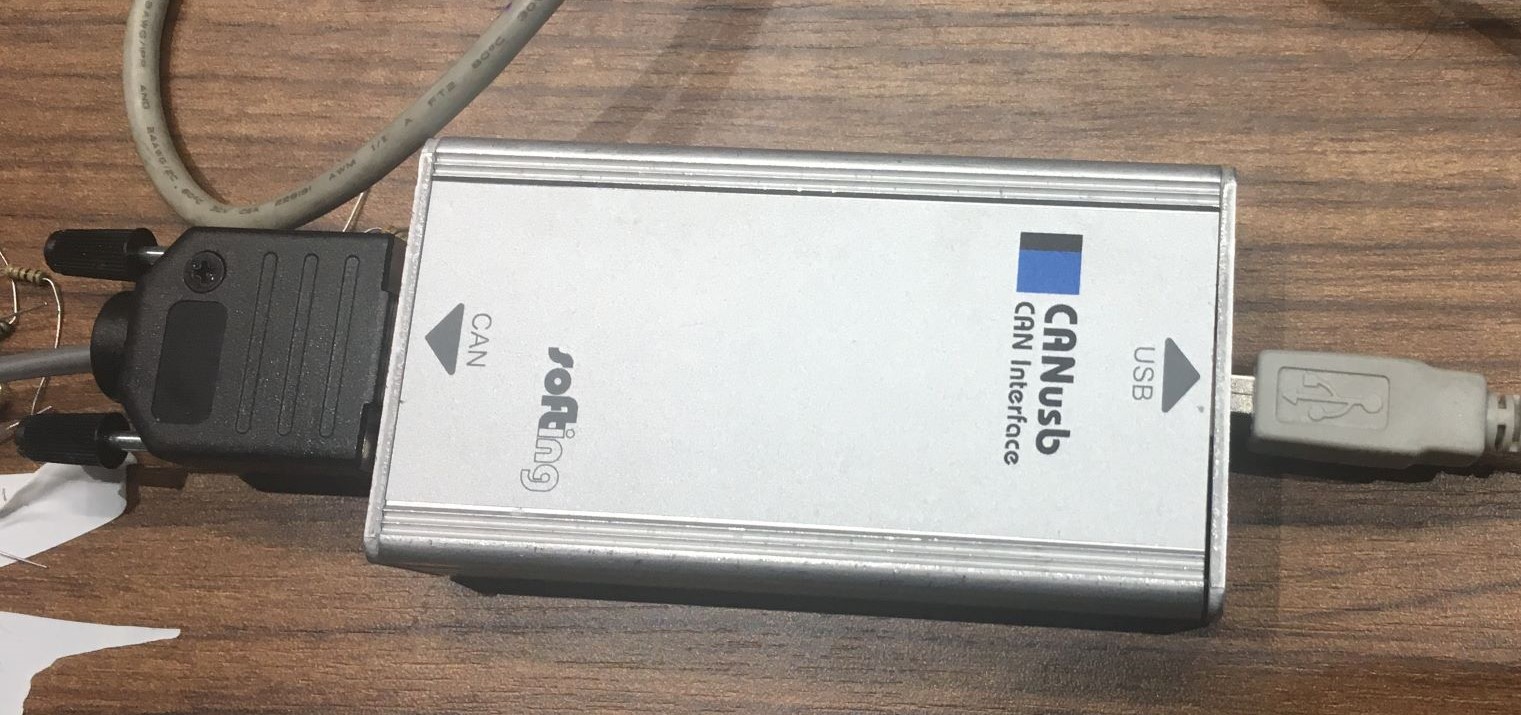

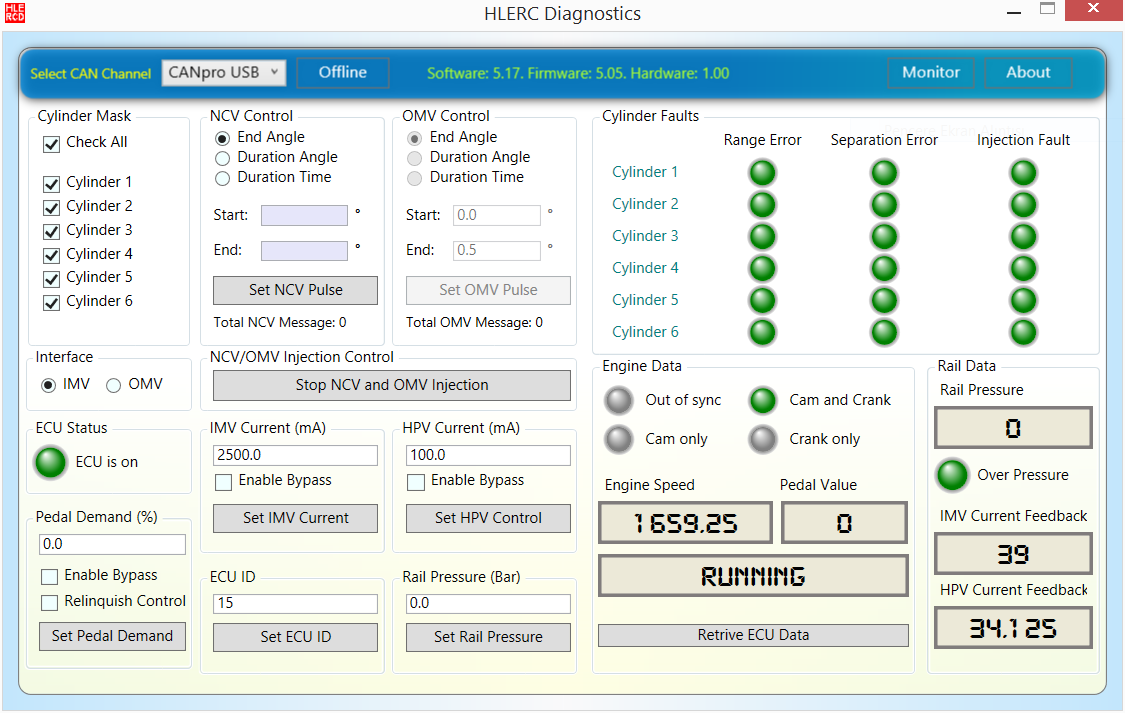

The testing ECU is manufactured by DELPHI. It is fed by a 24V source, drawing a maximum current of 20A. The ECU utilizes a CAN (Controller-Area-Network) interface output which is a digital bus containing data such as engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute), system state, current levels… To monitor this data; a CANusb interface (Figure 27) converter is used to connect the ECU to the monitoring PC. In the monitoring computer, there is a program named HLERC (High-Level External Remote Control) to monitor the data coming from the CAN interface; which is in turn coming from the ECU.

The ECU has two sensor inputs for Crank and Cam signals (Figure 28); which are connected to the MPC5744P board generating the waveforms. We also connected a fuel injection cylinder to the ECU as Cylinder 1; where the ECU will trigger the cylinder according to the RPM.

After checking the connections and making sure that the signals fed to the ECU (Figure 29) are in correct shape, especially the zero-crossings, we powered up the ECU. The generated crank signal has a period of 1.6 ms, which is 625Hz. The ECU calculates the RPM by looking at the crank signal. A crank signal of 625Hz means 625 teeth pass every second, 37500 teeth pass every minute, with 60 teeth in a gear, this gives us 625 RPM. Looking at the screenshot (Figure 30), we see that the ECU registers both crank and cam signals, measuring an RPM of 693.

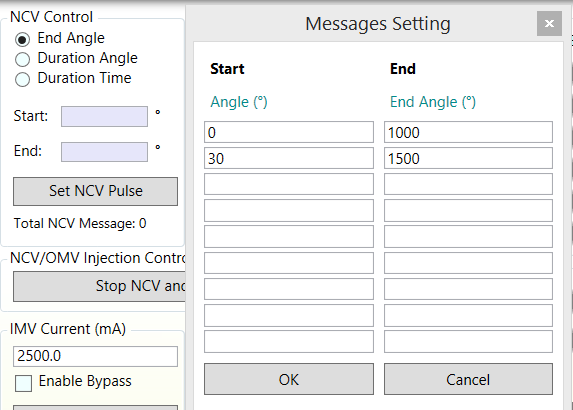

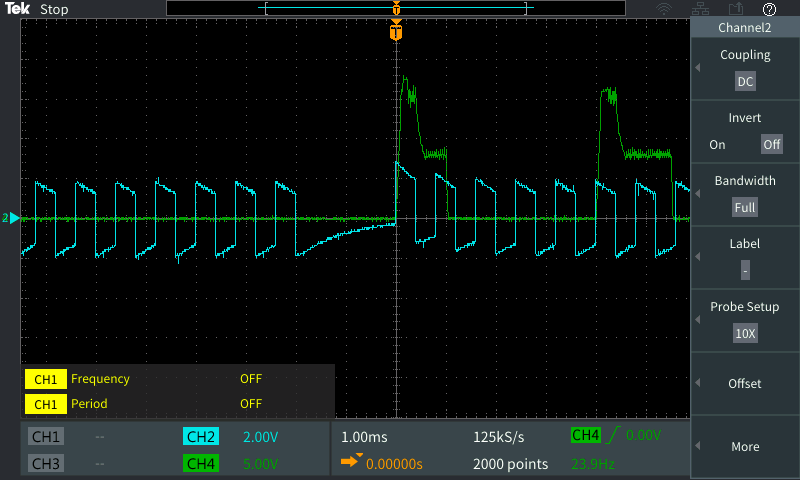

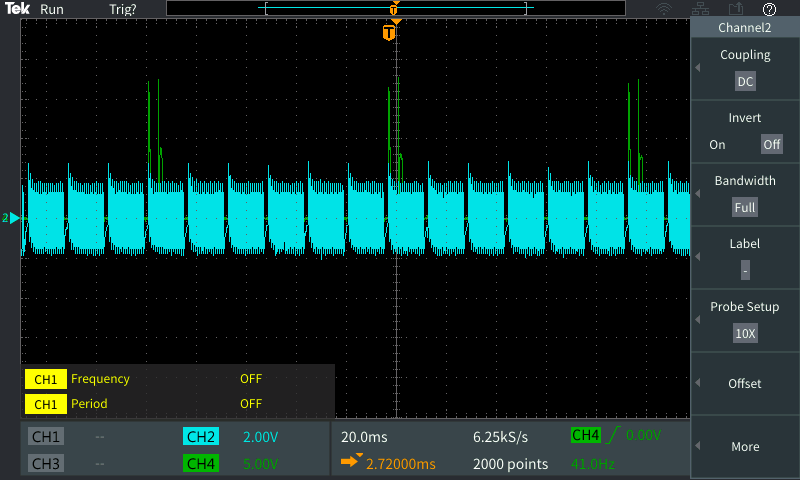

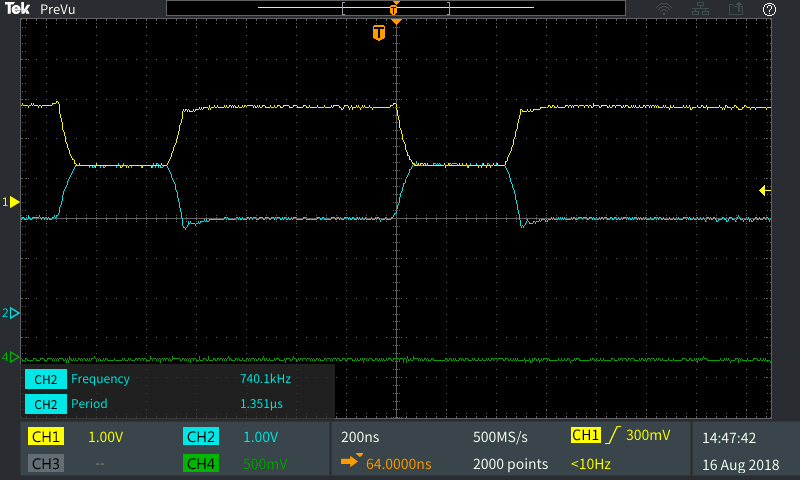

After observing that the ECU correctly registers the waveforms, we sent to the ECU, NCV (Nozzle-Control-Valve) pulse values. These pulses determine the injection timings and periods of the injector. When these were set, we were ecstatic to hear the clicking sounds from the injector. By connecting a current probe to its feeding cable, we observed that the ECU sent periodic bursts of 18A to the injector; to trigger fuel injection. Figure 31 shows these injector trigger pulses sent by the ECU (green) and the crank signal (cyan). Also, we can observe on Figure 32 that these bursts are sent every two full rotations of the crankshaft; which agrees with the theory.

The crank/cam signal waveforms we had generated did not need to have

a variable frequency, but I thought it would be more interesting if I

could connect it to the pot and hear the injection frequency and RPM go

up as I increased the frequency of the cam/crank signals. The default

SIMULINK blocks did not have the option to specify frequency as an input

port; nor did the PIT block included in the toolbox. After examining one

of the default clock blocks, I have seen that it was not so hard to

modify it to accept frequency as an input. The idea behind this clock

fascinated me with its simplicity and elegance; and warrants further

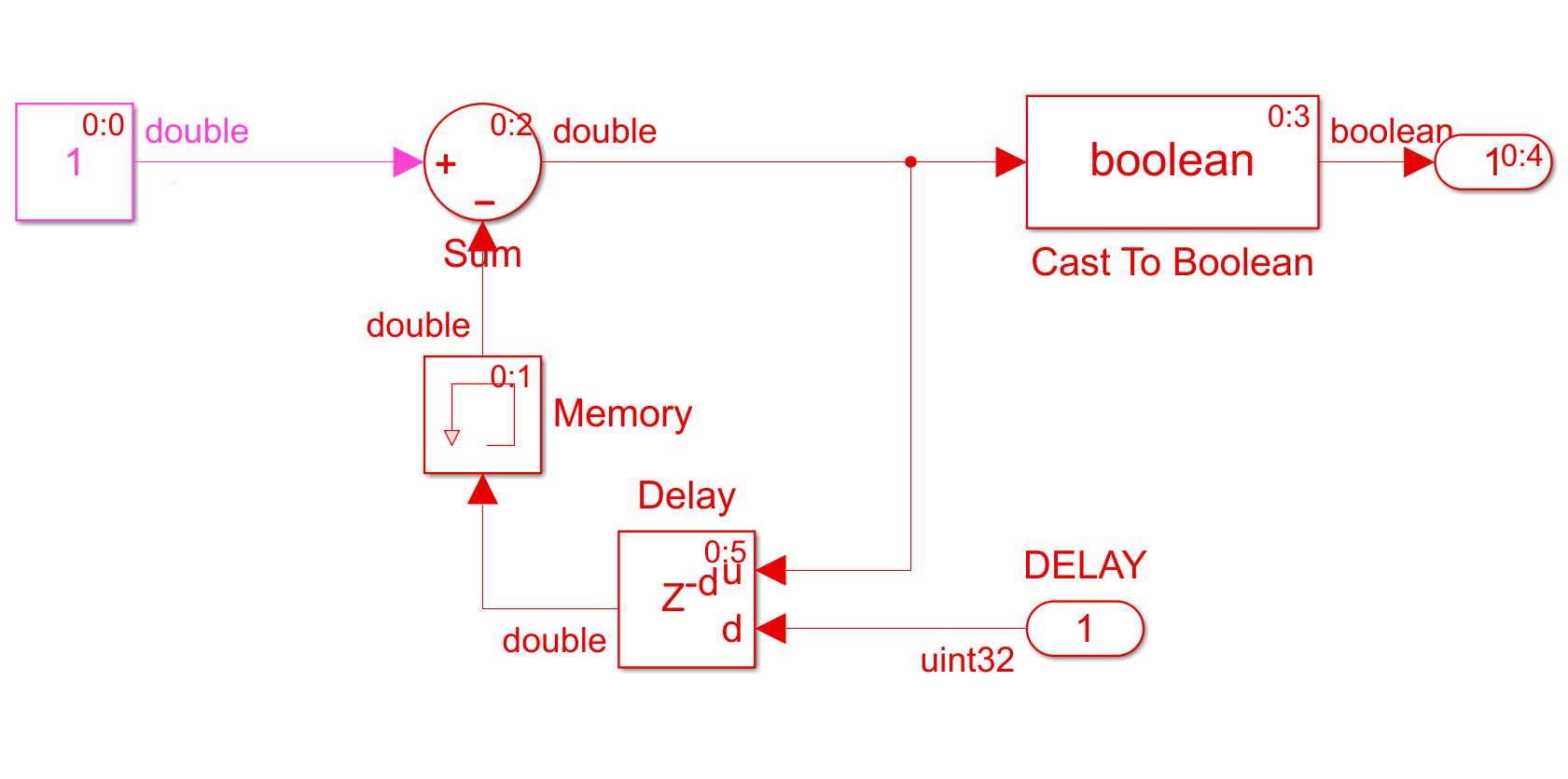

explanation. As can be seen in Figure 34, the idea is based on feeding a

constant value of ‘1’, and subtracting the result of the operation from

this constant in a feedback loop. The memory block is initialized as

‘0’, so the initial output of the system is 1 - 0 = 1. This

output 1 is fed back into the system as a subtraction, so

now the operation is 1 - 1 = 0. Again, this output is fed

back into the system, so the operation is 1 - 0 = 1. We can

see how it alternates between 1 and 0. To control this oscillation, one

can introduce a delay, so that the transition between 1 and 0 is timed.

This delay block is in the unit of “sample time”, and it, luckily, can

be set from outside. The last block is a “memory”, to ensure that the

system starts properly by setting an initial value of 0.

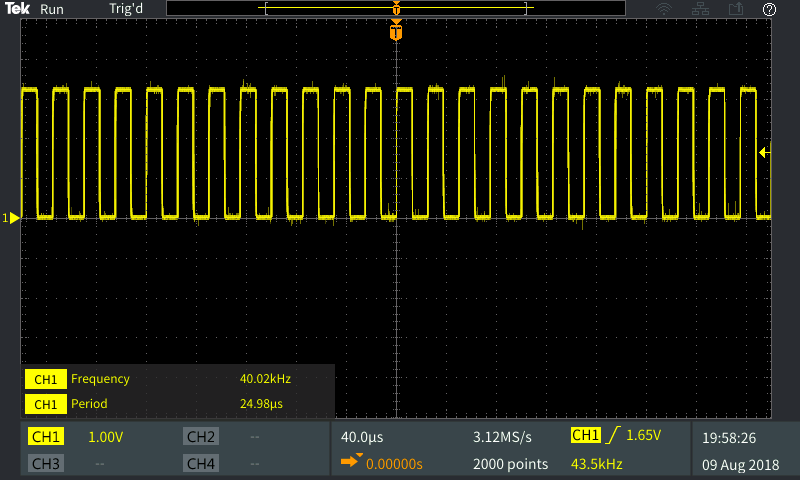

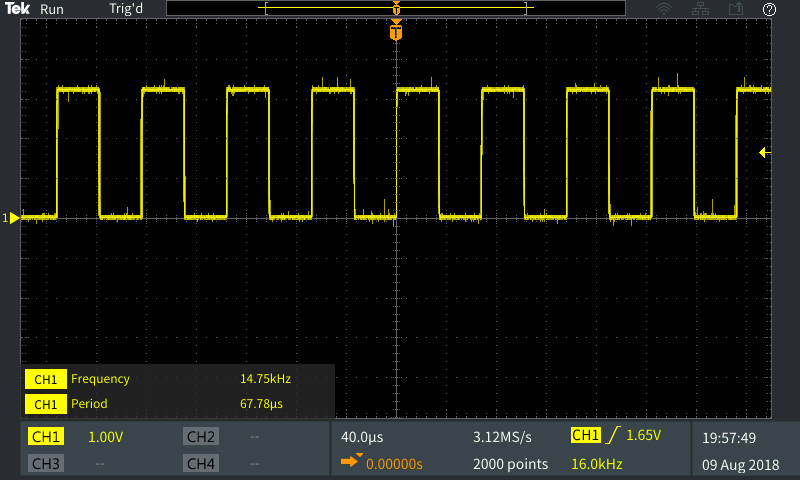

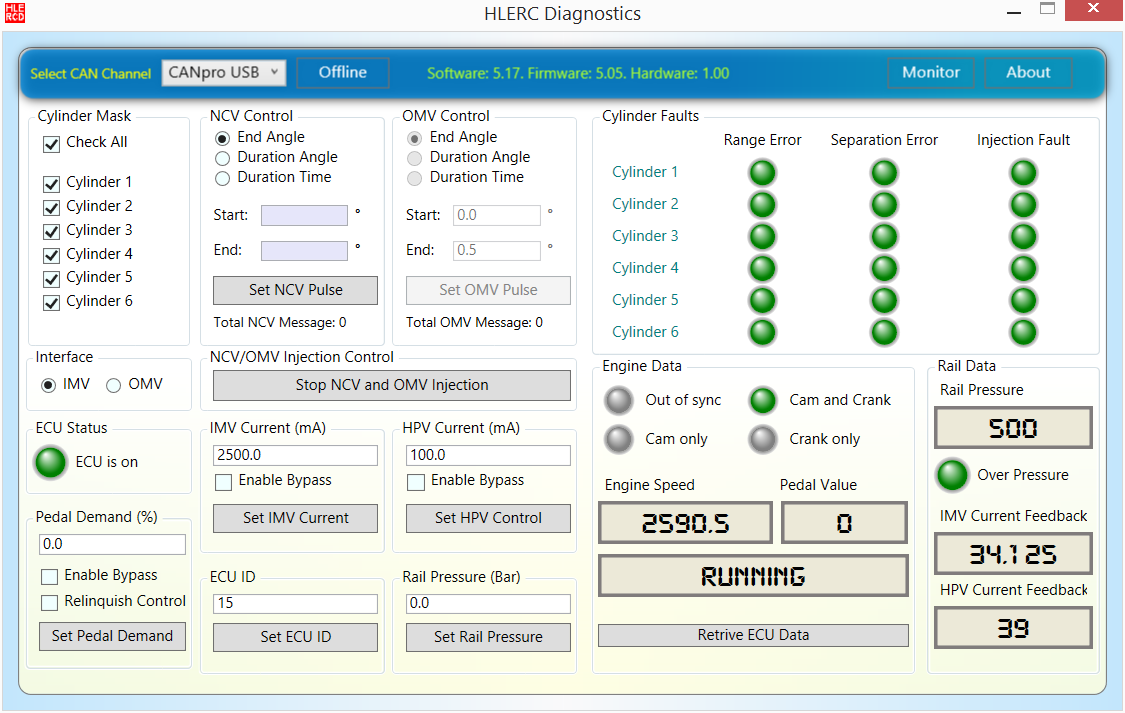

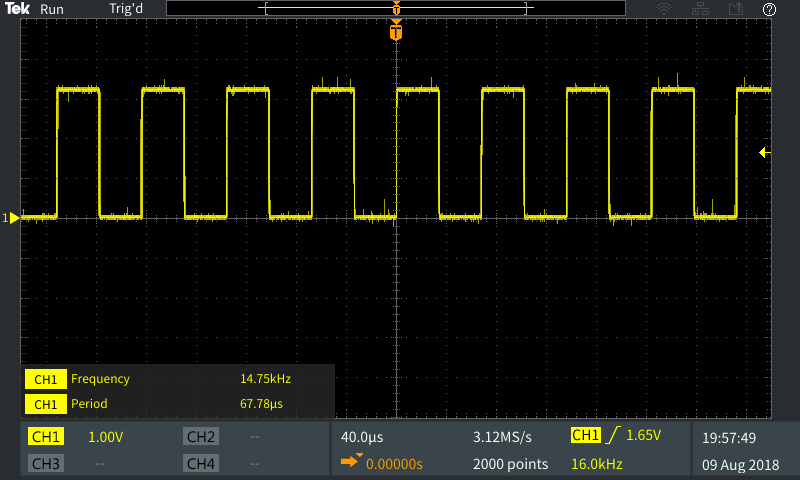

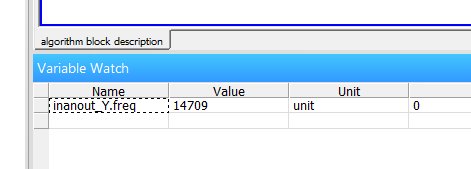

Figure 35 shows the final model, where the pot value is read; divided into 300, and fed into the clock frequency; the rest of the circuit is the same. This allows me to generate the crank/cam signals with instantaneous variable frequency depending on the current position of the pot; thus simulating a gas pedal. Figures 36 and 38 show different RPM values observed by the ECU when crank signal frequency is changed; which in turn depends on the position of the pot. Figures 37 and 39 show the crank signal waveforms at those RPM values

After correctly tricking the ECU into thinking that a motor is present, and thus concluding the main project, my supervisor Ahmet Bey gave and taught me some more projects and concepts to study further into the field of automotive, and model-based design.

We decided to look at the philosophies and the concepts behind SIL (Software-In-The-Loop), PIL (Processor-In-The-Loop) and HIL (Hardware-In-The-Loop); using the MPC5744P board and SIMULINK.

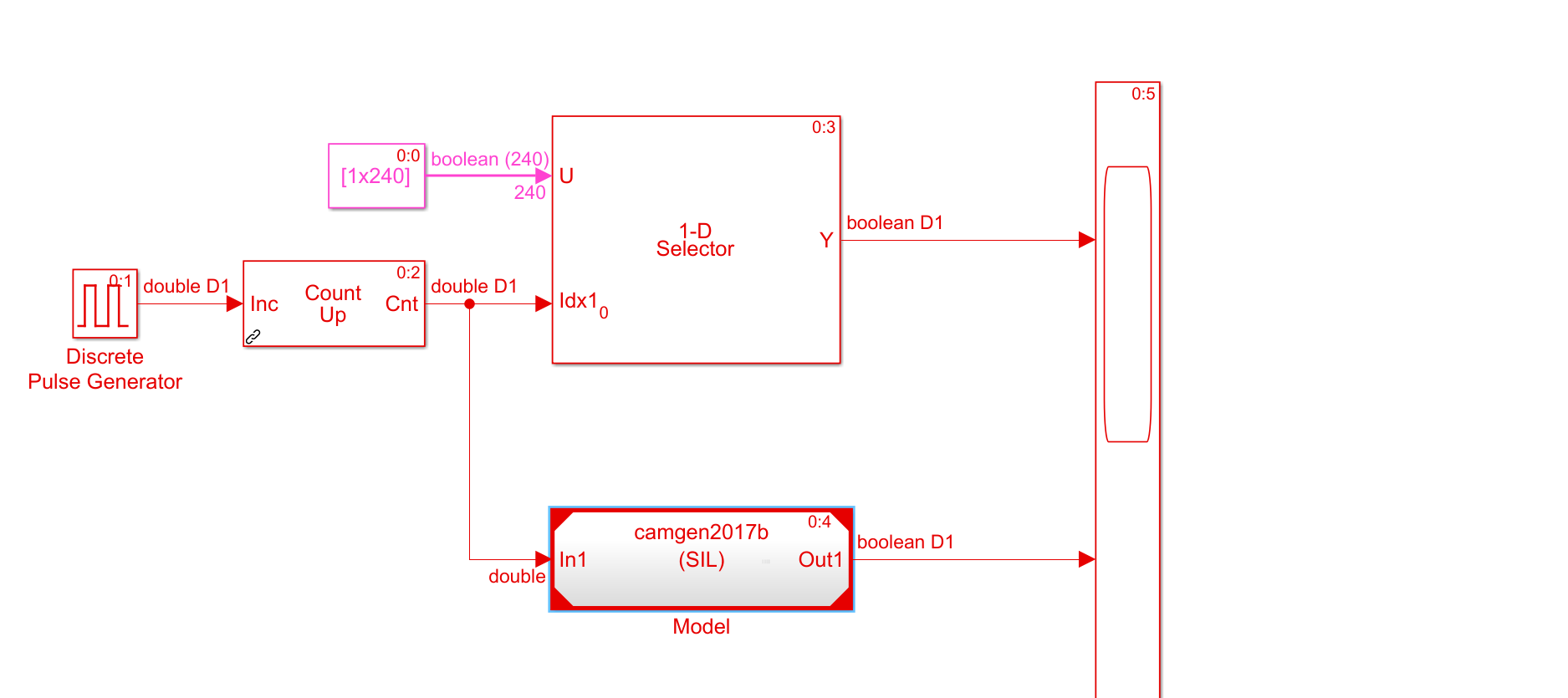

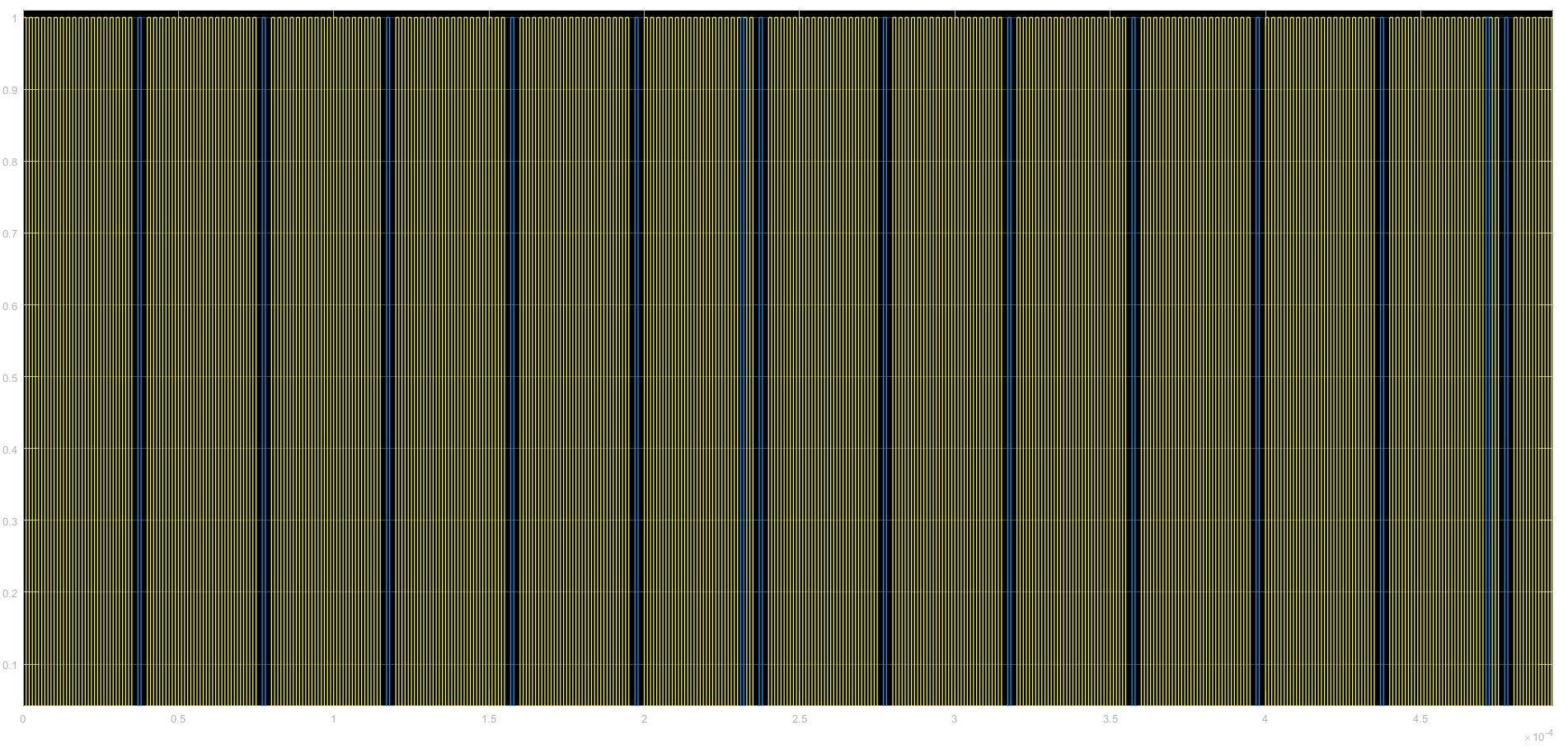

SIL is the first step towards building a program to implement it in hardware. Instead of directly downloading it into the hardware, you download it into a virtual version. The real hardware is emulated as a software block, and the code is downloaded to it. This helps you to see the problems which may arise, for example, incompatibility issues between your code and the hardware it is to run on. I have tested this using the already made model which generates cam and crank signals. The difference is that, however, no piece of code is sent to the board; the entire process is run on the host computer. I decided to implement the cam signal generation part as a SIL block. This means that the rest of the model will run as a normal SIMULINK simulation, while C code will be generated for the CAM part, and be “downloaded” into an emulated virtual version of the board MPC5744P. Figure 40 shows the model to generate the cam/crank signals, but the CAM signal generation section is modeled into SIL action. Figure 41 shows the resulting waveforms on the Scope block; as expected, the signals are generated without error.

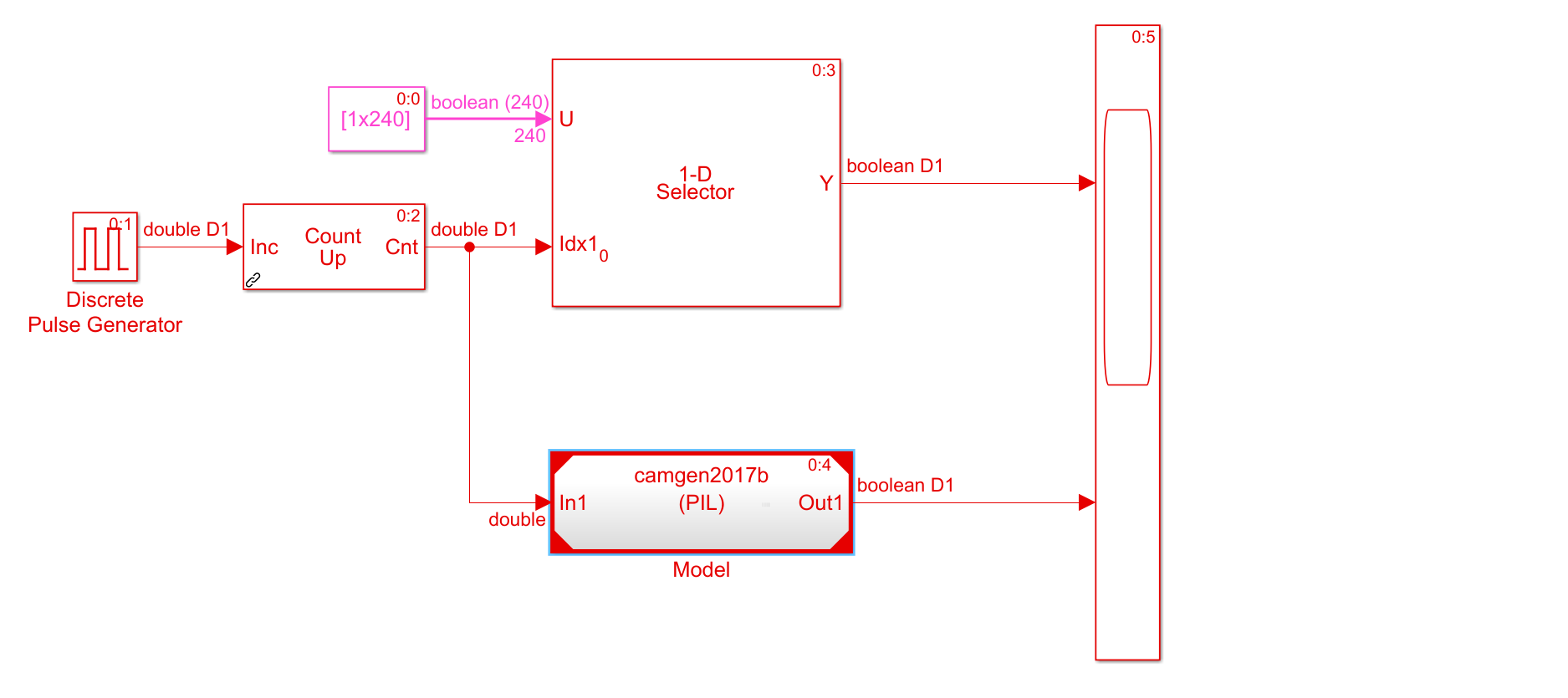

PIL is the second step. In this step only the processor of the hardware/board is used. The difference from downloading it onto the machine is that the code is not written on the board’s memory (flash/SRAM) and no input/output pins are used. This step is to ensure that the target processor is compatible with the code, without utilizing and involving other parts of the board. I used the same model, just changed the block to a PIL version. The process required additional compilers and commands, but I have finally got it to work. The results are identical to the SIL model. Figure 42 shows the model, and Figure 43 shows the observed waveforms.

HIL is the last step. The code gets downloaded onto the board’s memory and all hardware components are used. I already demonstrated that the crank/cam signal generation model works on the MPC5744P board, so repetition is unnecessary.

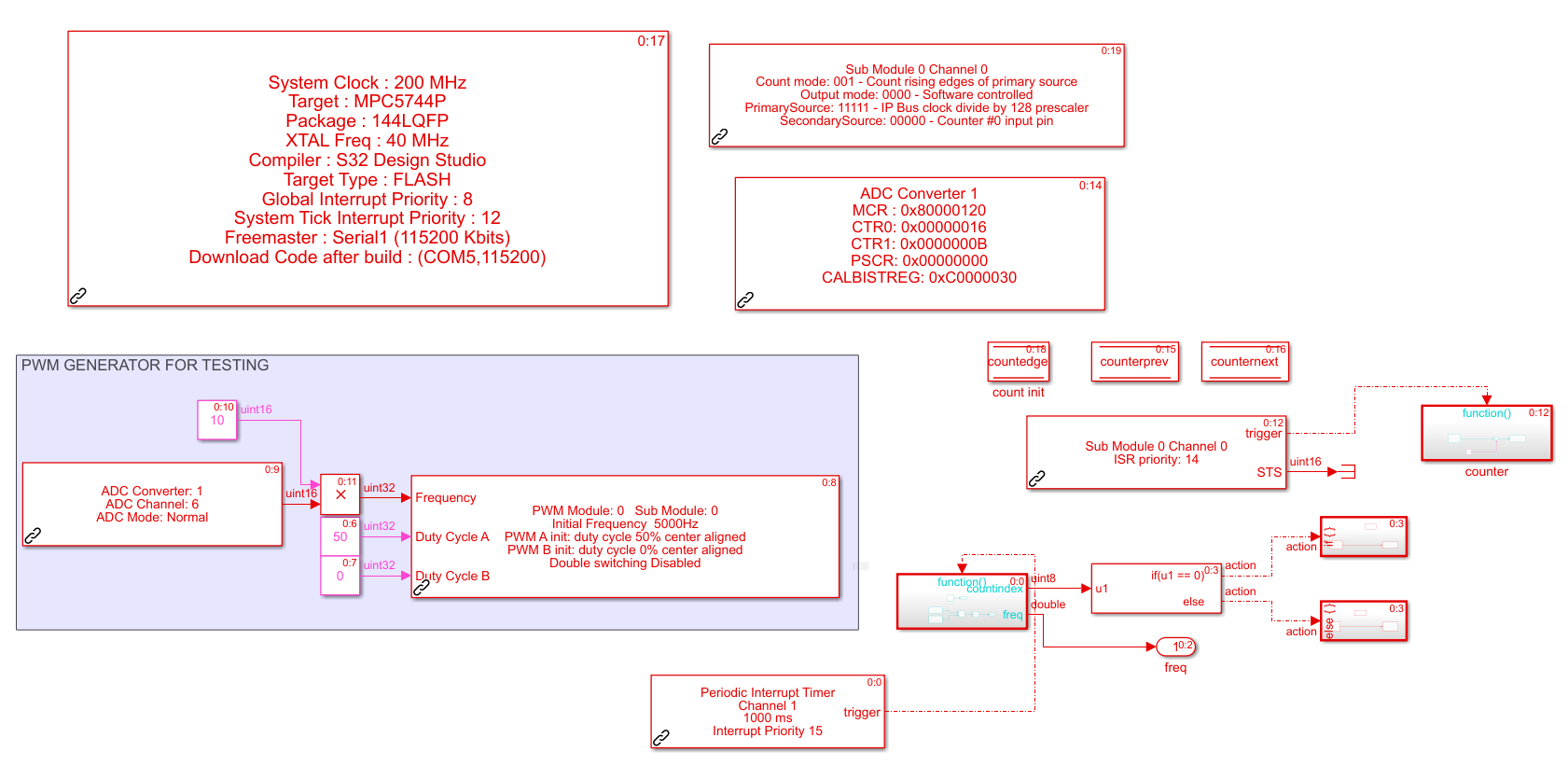

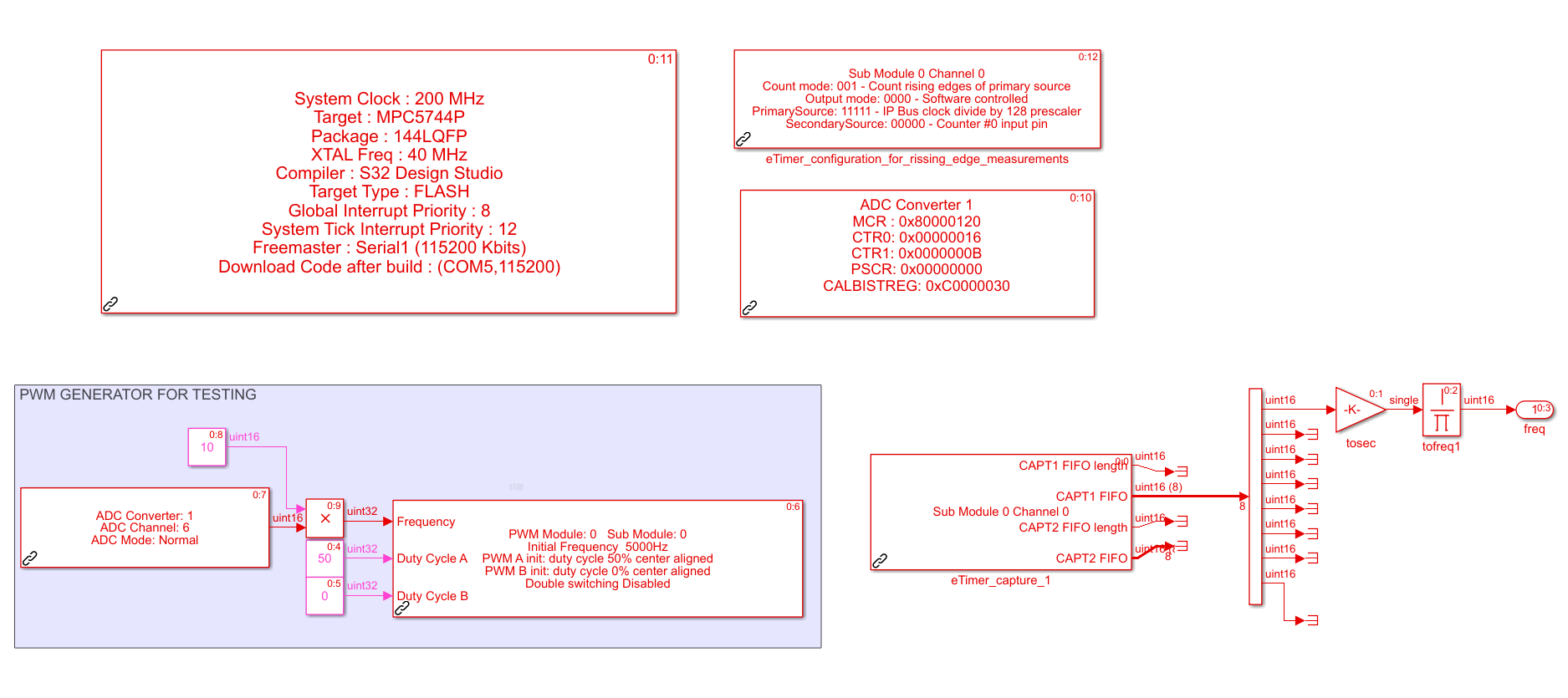

My next project was to design a model which reads a periodic signal from the input ports and calculates the frequency. I developed two methods for this, utilizing the hardware timer module “eTimer” for the purpose.

The first method counts the number of rising edges constantly, and each second; takes the difference between the consecutive two values. This gives me a 1-second resolution, which is acceptable; but the number of rising edges keeps increasing while the program is running, which is not desirable. The eTimer module generates a trigger each time a “capture” event occurs, and this capture event is defined as a rising edge detected on the input. This trigger is connected to a counter, which increments the value every time it is triggered.

The second method is more straightforward, it uses the FIFO (First-In First-Out) register of the eTimer module, which stores the “time” value of each capture event. This “time” value is not in seconds, because it is a built-in counter value run by the system clock (divided by a 128 pre-scale factor). This counter is programmed to reset at each capture event; so all I had to do was to take this counter value and convert it so seconds. This is easily done by multiplying it with a factor of “128/160e+6” corresponding to the pre-scale factor and inherent frequency of the system clock. The last step was to invert it, to the output frequency.

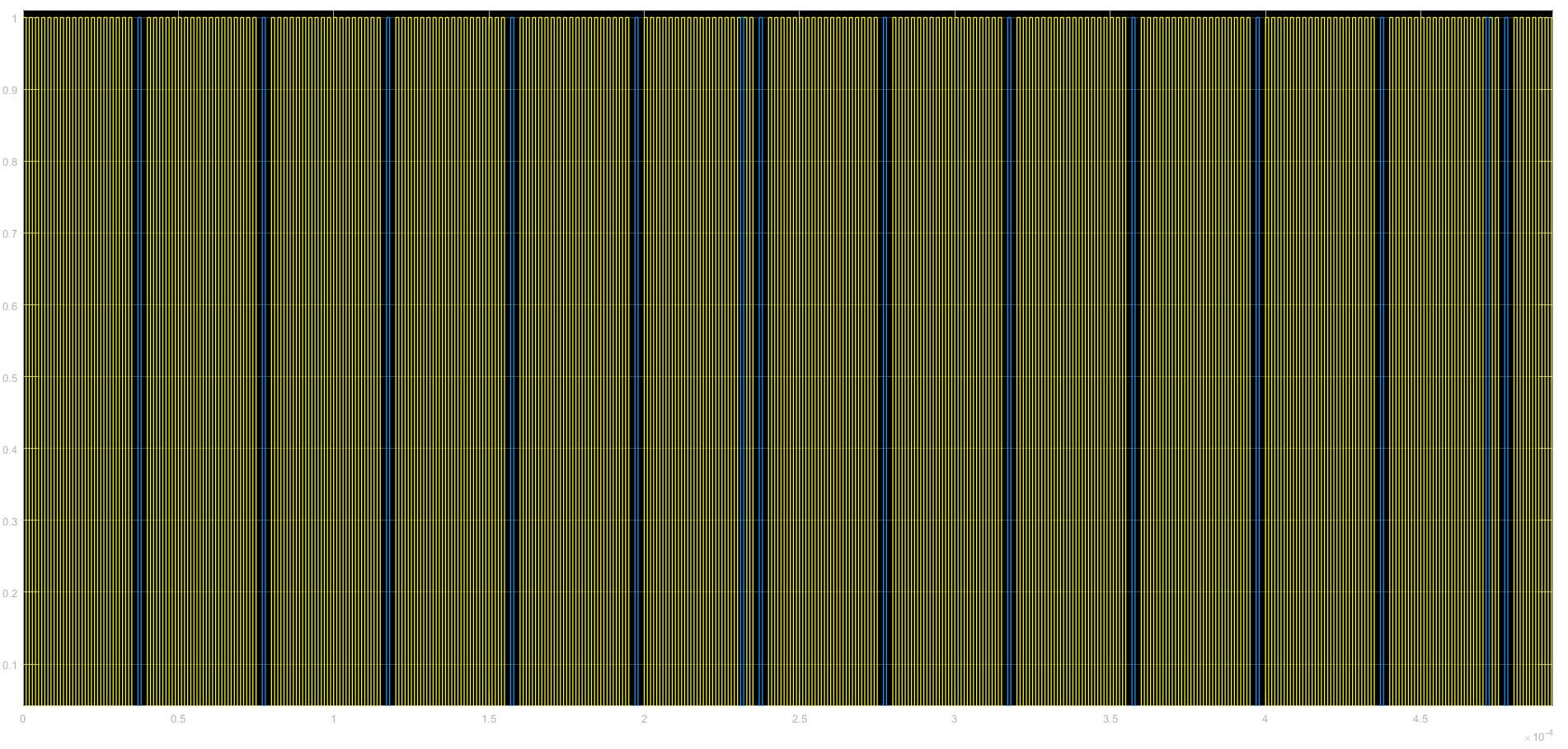

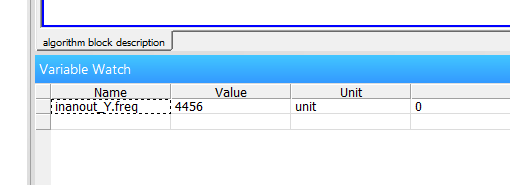

Since I had already developed a variable frequency PWM generator, I tested my frequency calculator models with it. I scoped the output frequency using FreeMASTER.

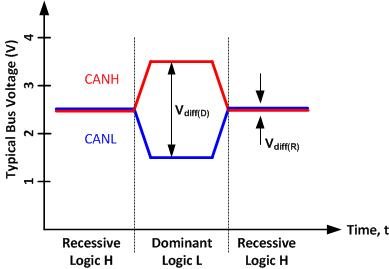

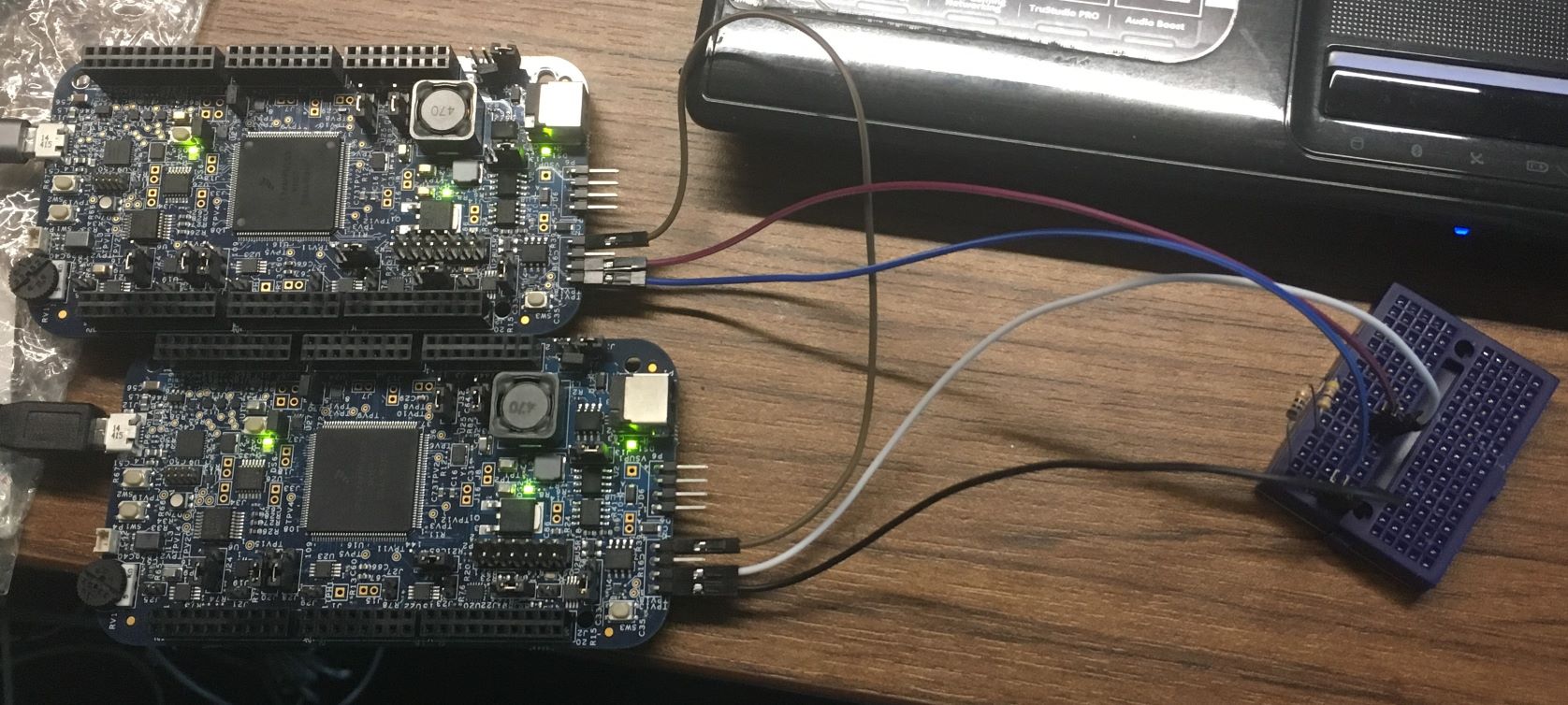

My next project was to understand the concepts behind the CAN (Controller Area Network) Bus interface. Quoting from the Texas Instruments application report: “The CAN bus was developed by BOSCH as a multi-master, message broadcast system that specifies a maximum signaling rate of 1 megabit per second (bps). Unlike a traditional network such as USB or Ethernet, CAN does not send large blocks of data point-to-point from node A to node B under the supervision of a central bus master. In a CAN network, many short messages like temperature or RPM are broadcast to the entire network, which provides for data consistency in every node of the system.” This method of communications is used widely in the automobile industry, especially between the ECU and the other systems of the car. I used this standard to enable communications and send data between the two MPC5744P development boards. Figure 50 shows the example of sent data on the oscilloscope. Figure 51 shows a typical CAN bus signal example, taken from the Texas Instruments community blog. As can be seen, the interface works by differential voltage between the HIGH and LOW pins. This eliminates the noise which can be caused from external electromagnetic fields, which are especially abundant inside a working vehicle.

Figure 52 shows the configuration where I connected two boards together with one as the transmitter and the other as a receiver. Every CAN bus connection must be terminated with a 60\Omega or 120\Omega resistor, I utilised 47+10\Omega in series.

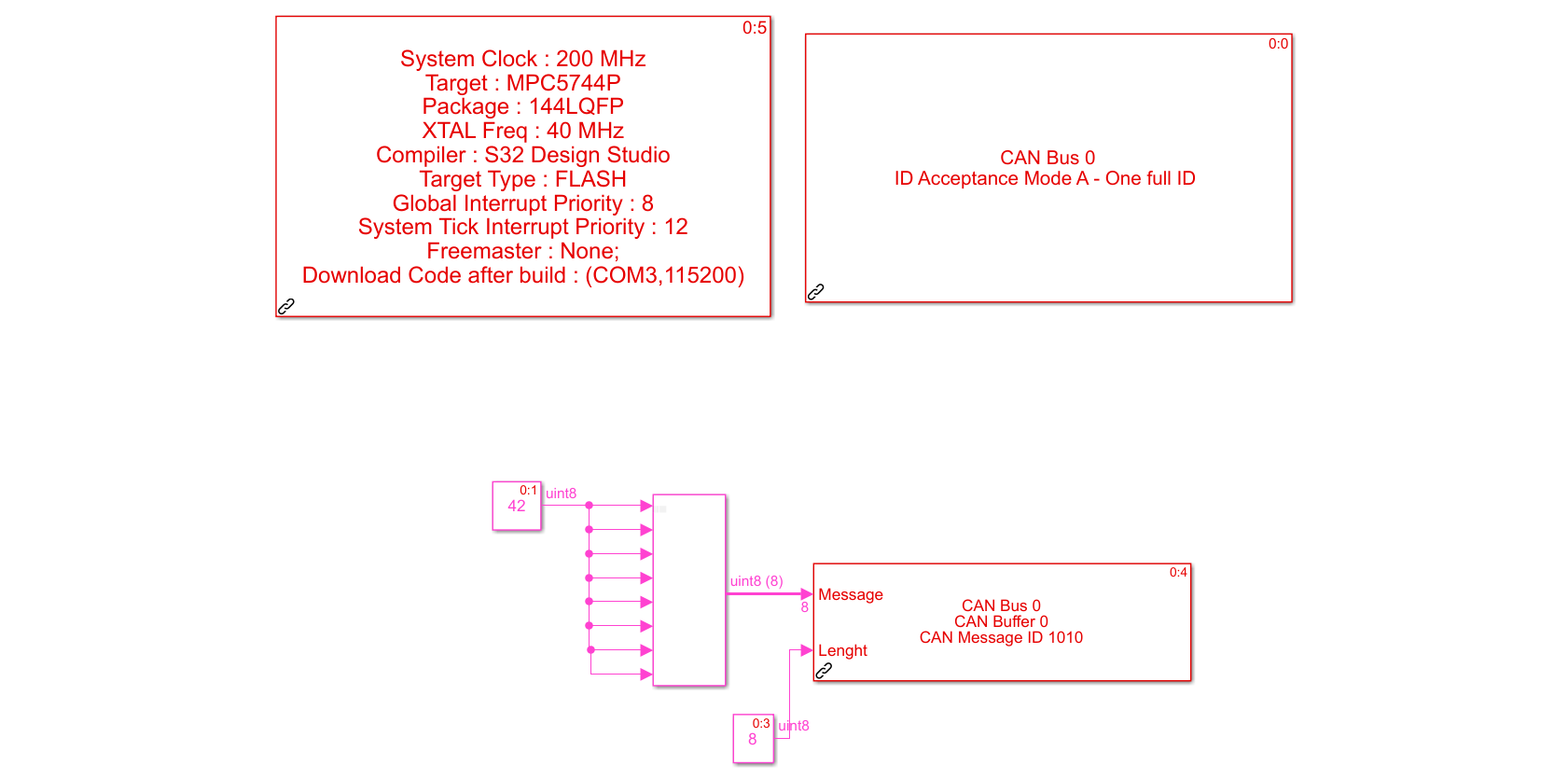

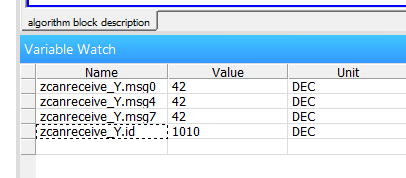

Figure 53 shows the transmitter model. The CAN bus transmitter block requires an array of 8 uint8 values, each set to the constant 42 with a multiplexer. The message is sent via the board’s transreceiver pin with the ID of 1010.

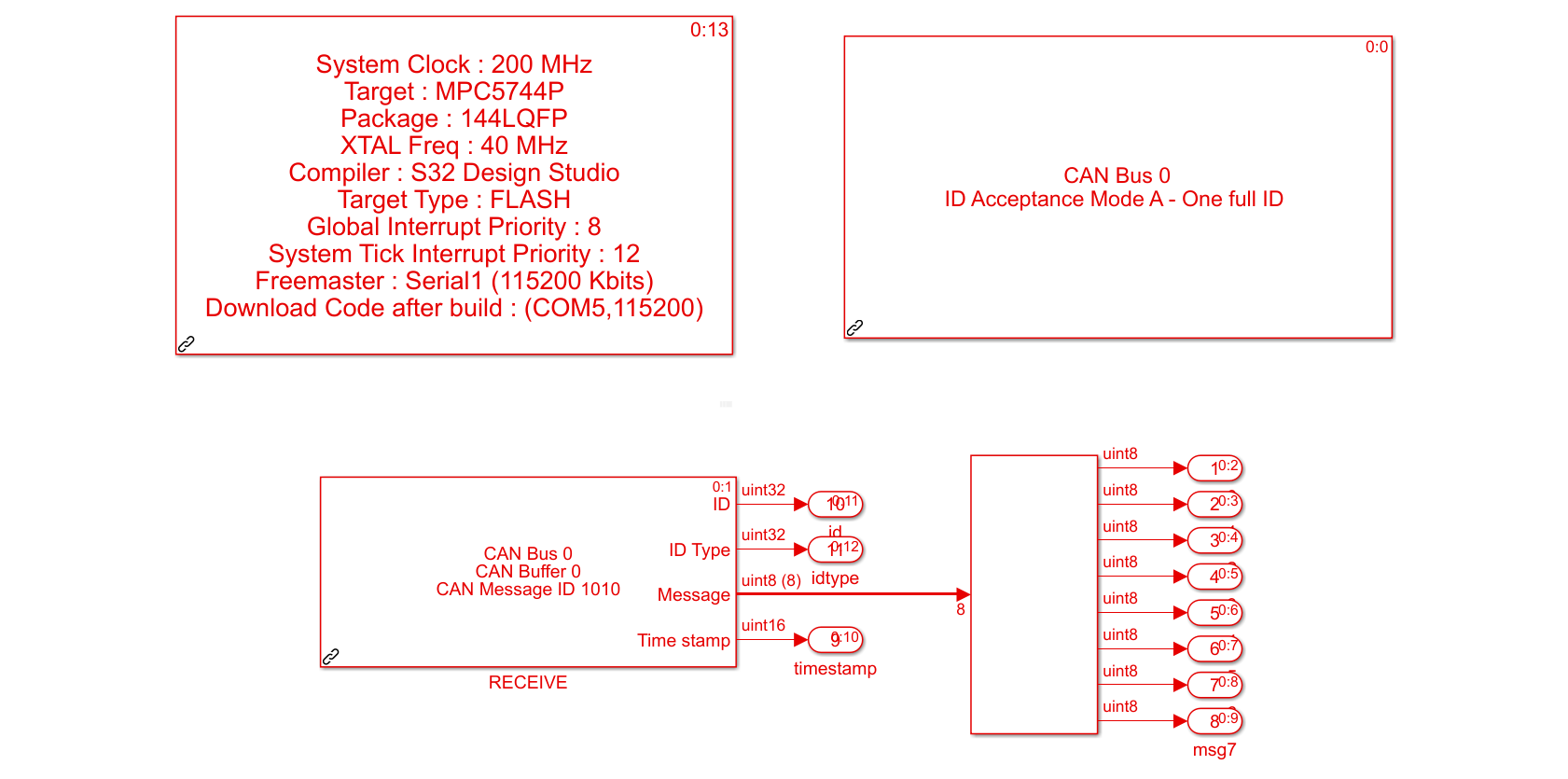

Figure 54 shows the receiver model. Set with the same ID, the receiver outputs the message, (again, as an array of 8 uint values), the sender’s ID, ID type and the timestamp of the sent message. The message is processed through a demux to read the individual elements of the array. These values are then monitored via FreeMASTER.

The results can be seen in Figure 55. The constant message “42” has successfully arrived at the receiver with the correct ID and every element of the array keeps the constant value.

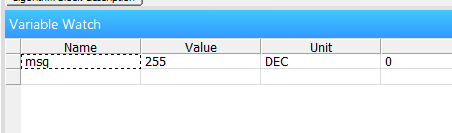

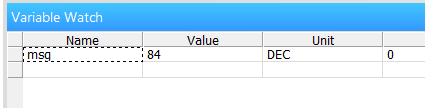

The next step was to transmit dynamically changing values since this is the usage scenario of the CAN bus interface; it is more significant and realistic. I have designed a model to transmit the value of the pot read from the ADC to the other board in real-time. The blocks remain the same, with the constant parts replaced by the output of the ADC; as done in previous projects. The results are again captured by FreeMASTER. As can be seen in Figures 56 and 57, the value of the message ranges from 0 to 255; as one would expect from a uint8 data type; and changes as the pot is rotated. This shows that almost instantaneous communication can be established between the different nodes of a CAN bus; which demonstrates why this method is heavily used inside vehicles between different modules.

It must be said that this internship was very instructive and educational. Apart from the technical gainings, which increased my familiarity with MATLAB, SIMULINK, model-based design, SIL/PIL/HIL processes, and programming microcontrollers; I have learned much about the current situation of the automotive industry in our country. I have observed and identified problems which I feel the need to share. One is the scarcity of engine part manufacturers in the country: to buy a simple fuel injector cylinder, a company has to go through complex legal/bureaucratic procedures to import it from countries such as Germany, USA, Italy… This obviously and sorely undermines any efforts to independently develop motor technologies. Another interesting thing I noticed was the lack of electrical know-how in the industry. Most of the engineers in this industry are of mechanical or industrial engineering origin; which are not familiar with the electronic control and microchip components required to build an engine. As the industry looks upon these things as magical black-boxes which they simply plug in; there is a significant need for more electrical engineers and people with this sort of technical know-how. Perhaps I will shape my career choices towards this industry, I am not sure but it certainly seems attractive to aid the country’s independent engine development sector in an important way.

Also, every .slx model that I designed is available on my GitHub repo: EEE299SLXMODELS